Investigative

Two out of three summer interns from seven top newsrooms came from among the most selective colleges in America, our analysis shows.

Two out of three summer interns from seven top newsrooms came from among the most selective colleges in America, our analysis shows.

Published August 2, 2019

Members of the media run across the plaza at the Supreme Court holding decisions on June 25, 2015, in an official tradition referred to as the "running of the interns." (AL DRAGO/CQ ROLL CALL/GETTY IMAGES)

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

65% of summer interns from a group of publications including The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, NPR and Los Angeles Times, came from among very selective universities in the nation.

The New York Times, The Washington Post and Wall Street Journal especially recruited from the top 1% of schools ranked by selectivity.

Theodore Kim, the New York Times’ director of newsroom fellowships and internships, tweeted in March what he called his “super unscientific opinion on which U.S. schools churn out the most consistently productive candidates.”

Kim listed his top 26, ranking them by best — Columbia, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, Yale — then two tiers of honorable mentions. He noted that “there are many great schools/students beyond these.”

Within days, the dismay among other journalists and academics crescendoed.

“Please understand how your list could be demoralizing to a lot of young journalists,” tweeted Will James, a reporter for Seattle public radio station KNKX-FM, warning that the sentiment behind the list risks “reinforcing old, crusty structures.”

“Dear future journalists … If you are relentless, a good listener, curious and work hard no one will care about where you went to school,” tweeted Jackie Kucinich, Washington bureau chief for the Daily Beast.

“I went to a public university (not in the top tiers),” tweeted Tawnell Hobbs, a former colleague of Kim’s who attended University of Texas at Arlington. “I worked at several newspapers, and now I’m The Wall Street Journal’s national K-12 education reporter.

She added: “Nope, no pedigree — just a lot of hard work.”

When asked why she tweeted, Hobbs said she saw “students who seemed defeated. I felt like I needed to respond and let students know that, ‘Hey, here I am. This is what happened to me, and if you work really hard this can happen to you.’”

Two days after his post on the subject, Kim tweeted, “I’m sorry if I sounded elitist and narrow. That wasn’t my intention.”

He added, “If you follow this feed, you know I strongly believe that your work/values define you, not your school. But I tweeted it, so I’ll own it.”

Kim declined numerous interview requests over the last month.

“I don’t see any benefit to talking more about this,” Kim said at the Asian American Journalists Association’s opening reception in Atlanta Wednesday.

In the blowback to the tweets, an important conversation started.

Our team of four reporters decided to find out whether Kim’s tweet reflected a reality for incoming journalists seeking internships at top publications. We wanted to answer this question: Do interns predominantly come from a few select universities?

We conducted an analysis of summer interns from seven news organizations from the summer of 2018.

In all, we collected data from about 150 news interns from the summer of 2018 who worked at The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, NPR, Politico and Chicago Tribune.

We chose news organizations with high print circulations that have similar internship programs. We also added some organizations that are dominant in broadcast and online platforms.

We explored looking into internships at other digital-first news websites. BuzzFeed did not have a formal internship program last summer, and we could not reach a formal internship coordinator for Vice or Vox.

We tried sending a survey to over 150 interns we identified; about 70 responded and we completed follow-up interviews with 16 of them. We also used social media to crowdsource responses from current and former interns to gain broader insights — such as whether they got paid and if they felt financial pressure.

Managers at The New York Times, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and Politico either posted their intern lists publicly or gave them to us when we asked.

Executives at The Wall Street Journal, NPR and Chicago Tribune declined to provide us their list of interns. But we were able to obtain and confirm the names of the interns and their school through interviews, LinkedIn searches and survey results.

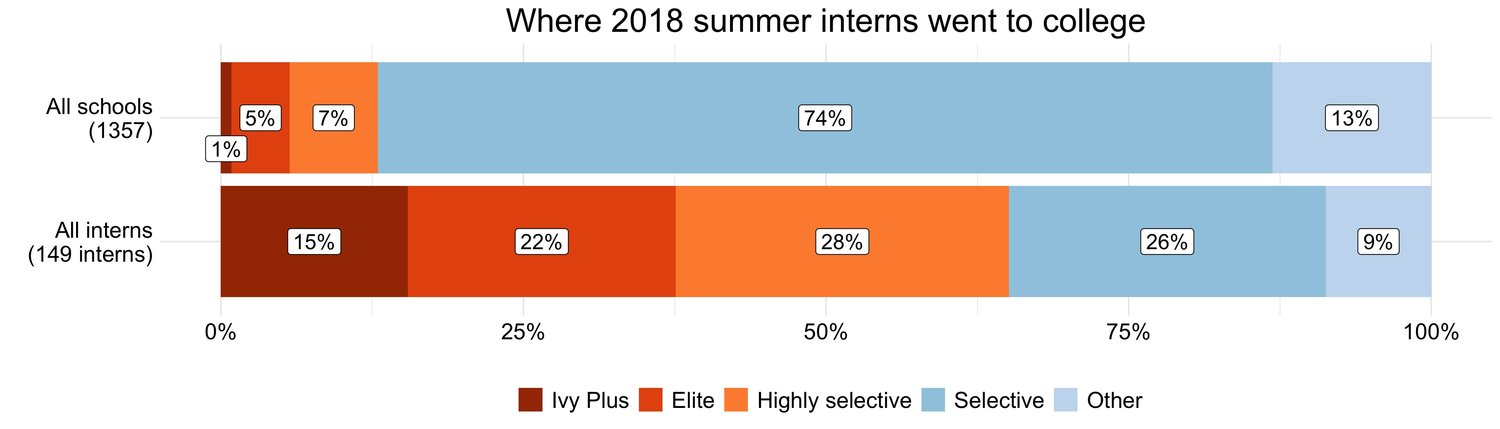

Our analysis shows that most summer interns at these seven news organizations came from America’s highest selective universities.

We found that 65% of interns from those seven organizations attended a group of intensely selective universities that make up just 13% of U.S. four-year colleges.

This group of intensely selective universities includes these three tiers:

“Ivy Plus” (combining the eight Ivy League schools with Stanford, MIT, Duke and the University of Chicago), which represent the top 1% of the nation’s four-year colleges;

“Elite” universities such as Northwestern and NYU. There are 65 in this category, which represents 5% of the nation’s colleges; and,

“Highly selective” schools such as UC Berkeley and University of Florida. There are 99 in this category, which represents 7% of the nation’s colleges.

For our analysis, we consider all universities in these three tiers — the top 13% most selective four-year colleges nationally — as “intensely selective.”

See where your university system or college falls within the categories.

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

The remaining schools were considered “selective” or “nonselective or other,” because they were international schools, newly established, or otherwise had too little information to determine their selectivity. “Selective” schools represent 74% of the nation’s more than 1,300 four-year not-for-profit schools; the remainder make up the last 13%.

Examples of “selective” schools include Arizona State, Cal State Northridge, Indiana University, San Francisco State University and University of Missouri.

By news organization, here’s what we found for the news intern class of summer 2018. See the summary statistics that generated the following graphs.

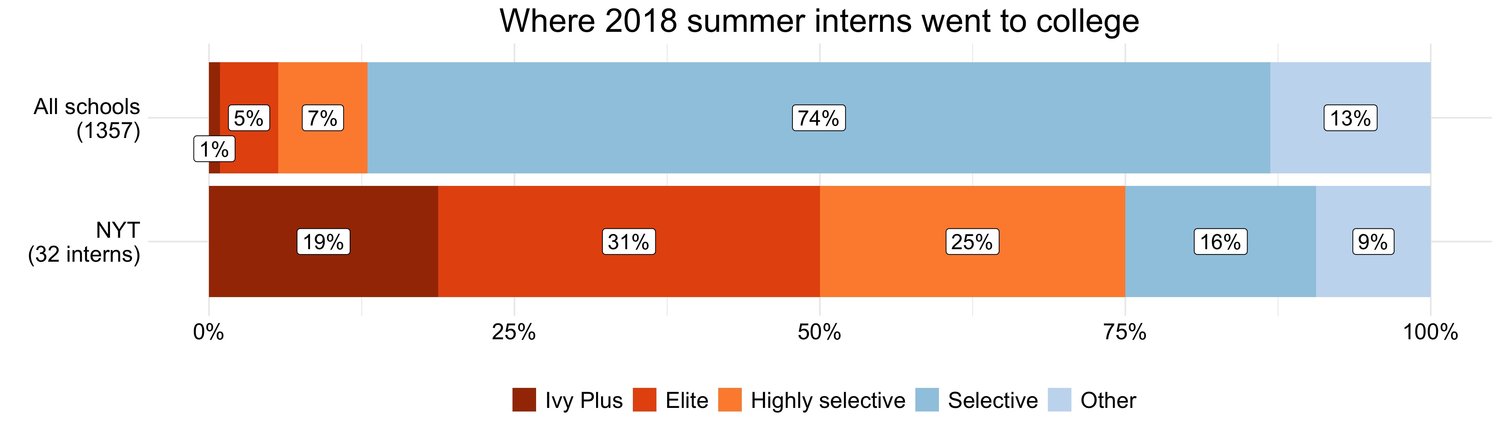

New York Times

About 75% of The New York Times’ 32 interns in summer 2018 came from intensively selective universities. About one in five came from “Ivy Plus” schools.

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

A New York Times spokeswoman, Danielle Rhoades Ha, released the following statement as we reported this story, but before we completed our analysis:

“We recruit the best-qualified individuals from a diverse candidate pool who have a broad range of educational and professional backgrounds. Our newsroom fellowship program selects journalists with some experience who are early in their careers, including recent graduates of college and graduate school.

“We have a global audience and believe it’s crucial that our workforce reflects the diversity of our audience,” she said. She also shared with us a link to more information about The New York Times’ diversity statistics.

We requested a follow up interview after we completed our analysis this week, and shared our results. We did not receive a response to that request.

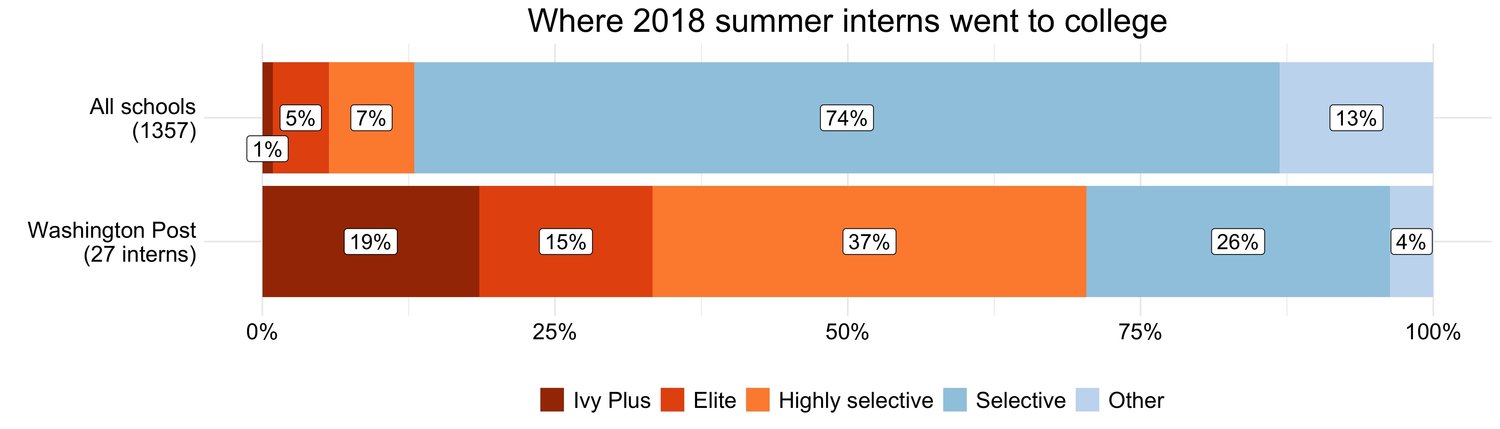

Washington Post

About 70% of the Washington Post’s 27 interns in summer 2018 came from intensively selective universities. One in five came from “Ivy Plus” schools.

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

As we were reporting the story, we spoke with Tracy Grant, the managing editor for standards and ethics at the Washington Post in charge of hiring and development.

She said the paper looks at a number of parameters for diversity when it comes to hiring interns. These include geographic diversity, the types of schools — finding a mix of public and private schools — and students who are juniors, seniors or graduate students.

The Post, which Grant said receives around 1,500 applications a year for its summer internship program, usually accepts around 25 to 28 students. During the application process, she said the Post does look at the students’ body of work and their references, but they put a large emphasis on the autobiographical essay that applicants submit.

Grant said it is the candidate who “creates an amazing scene” or “tells the story that makes you want to meet that person,” that makes them a strong applicant.

She said while she feels like they often do find students coming from specific schools — such as Indiana University, Western Kentucky, University of Maryland, Syracuse and University of Southern California — she said the Post chooses interns, not schools.

Grant said that while she does see some schools produce students with specific strong skills — for example, Indiana University students being strong storytellers, or Western Kentucky having solid visual journalists — others, like USC, send them well-rounded candidates.

After we completed our analysis this week, we shared our results with Grant and asked for a followup interview. Grant said she did not have anything further to say.

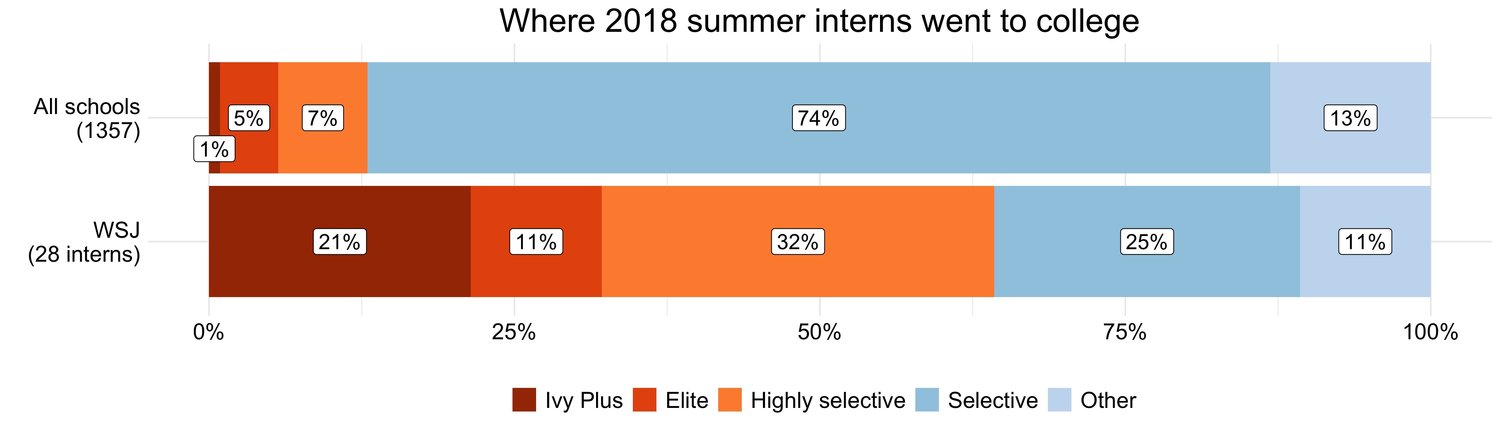

Wall Street Journal

About 64% of the Wall Street Journal’s 28 interns in the summer 2018 came from intensively selective universities. More than one in four of the interns came from the highest ranked category known as “Ivy Plus.”

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

Sarah Rabil, assistant managing editor for talent since June 2018, said the Journal’s internship is “highly competitive,” but that their “goal is to bring in the best interns with a diverse array of skill sets, backgrounds and perspectives.”

Rabil said she did not choose last summer’s interns, but did oversee them once they arrived.

“We strive to get the word out about our internship program far and wide, but ultimately we can’t control who decides to apply,” Rabil said in an email. She said she looks for ways to get on the radar with more students and make a conscious effort to visit a broad arrange of campuses across the country.

Rabil said the Journal identifies schools that can improve the diversity of early-career journalists. She pointed to a business journalism exchange program the Journal has with Morgan State, a historically black university.

“Because we see internships as seeding our potential future hiring pipeline and that of the industry, it’s important that we strive for diversity, in all facets of the word,” Rabil said.

NPR

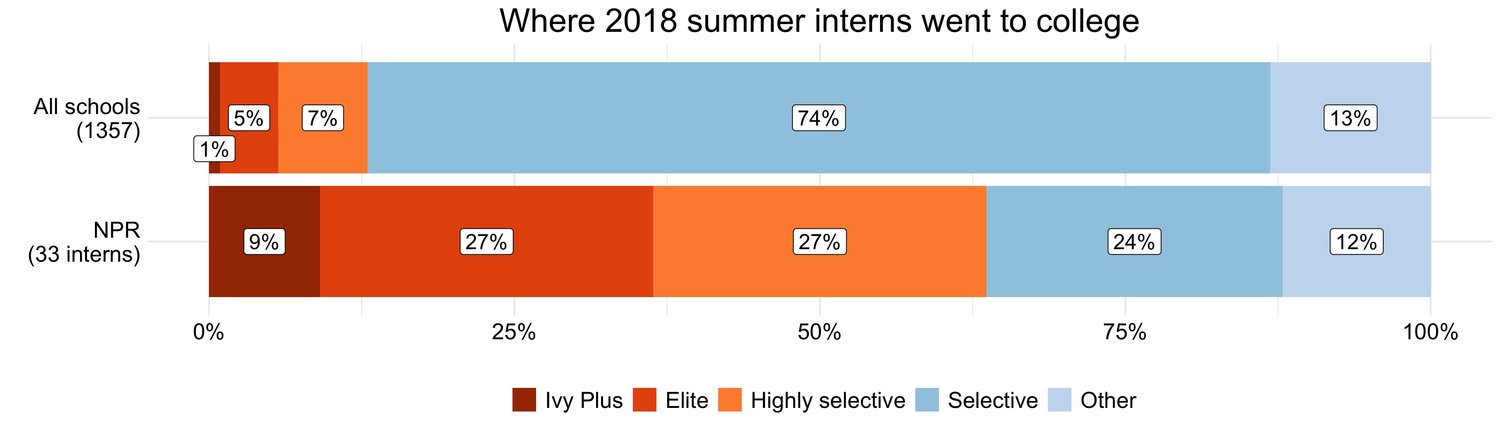

About 64% of NPR’s 33 interns in summer 2018 came from intensely selective universities. About one in 11 attended “Ivy Plus” schools.

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

NPR spokeswoman Isabel Lara declined an interview. In an email, Lara wrote that she could not speak to our findings because NPR does not share personal information about its staff.

She also shared with us a statement with demographic information about the 2018 interns.

“We have a highly diverse & talented pool of interns each year. They represent a broad range of colleges & universities across the country, which is different each semester,” she wrote.

She wrote that 75% of their 2018 newsroom interns — summer, fall and winter/spring — interns were female. As for race, 44% were white; 19% were Asian; 10% were black; 15% were Hispanic.

Los Angeles Times

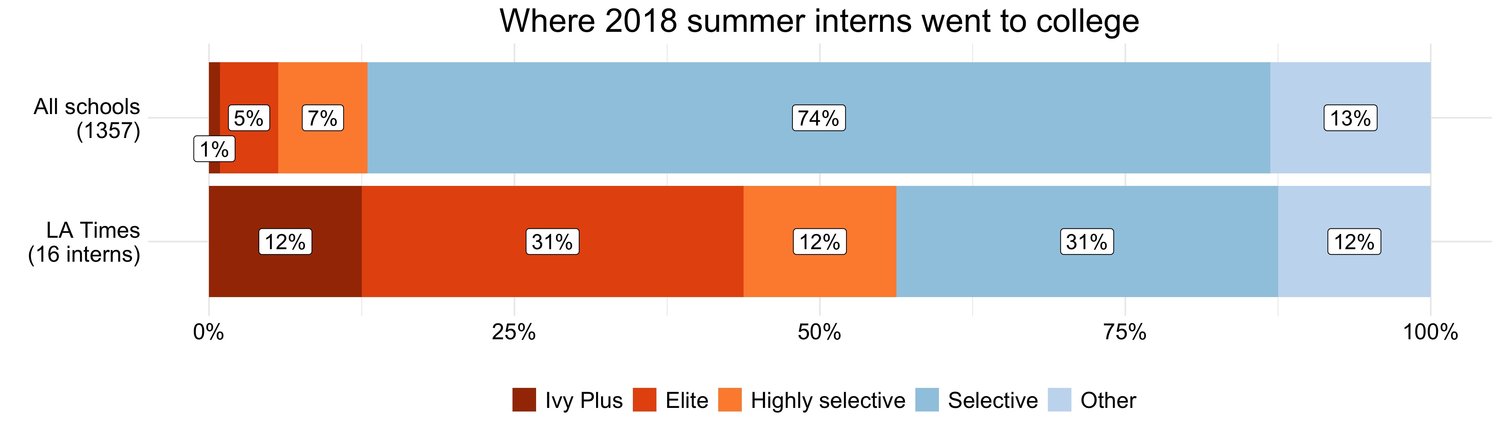

About 56% of the Los Angeles Times’ 16 interns in summer 2018 came from intensively selective universities. About one in eight attended “Ivy Plus” schools.

Source: Voices reporting (Credit: Amanda Zhou)

After we analyzed our data, we spoke this week with Tracy Boucher, the Los Angeles Times’ director of news development. She said she creates a list of finalist candidates and the section editors choose their interns.

She said the biggest thing she looks at is work experience. “I don’t care where anyone goes to school, I really look at the work and experience — it’s always first and foremost,” Boucher said.

Boucher added that the Los Angeles Times does “tend to take more students from the schools that have the stronger journalism program, because those students do tend to have the experience and skill sets we’re looking for.”

She said the 2018 class was smaller and different than the other summer intern classes — unusual because of the newspaper’s purchase and a move to a new headquarters. She suggested a more representative look would consider many years of interns.

Boucher also said some interns were chosen or narrowed down by other organizations; for instance, the Dow Jones News Fund selects a copy editing intern, and a few interns have come through programs associated with their universities, such as USC and Notre Dame.

“We’re obviously looking for people that want to be journalists,” Boucher said. “So you have to believe that they sought out those opportunities to apply to the schools that have the strong program.”

Boucher said Kim’s tweets sparked a conversation in the Los Angeles Times newsroom about where it recruits candidates.

“I think there’s no shame in students seeking out the best programs for what they want to do professionally,” she said. “We’re looking at the experience, so I guess the students that get more experience through these more elite programs are going to have a slight edge.”

That said, she added, “We’re very cognizant of trying to get people from across the country — all sorts of different levels of socioeconomic backgrounds,” she said. “We love having a newsroom that reflects the community… the more we can do that, the better.”

Politico

Politico and the Chicago Tribune had far smaller classes of interns in summer 2018.

Half of Politico’s six interns came from intensely selective universities. One came from an “Ivy Plus” school.

Margaret Slattery, one of the three people in charge of Politico intern selection, said Politico aims for their intern class to come from a variety of school types — public and private, smaller and larger campuses.

“We want to make sure we are offering opportunities to people from different backgrounds,” Slattery said.

“There is a tradition of certain schools of being pipeline for journalism, but we don’t want to limit ourselves to those places, because other schools might have really promising individuals that we should be talking to you and looking at.”

Chicago Tribune

Three of the Chicago Tribune’s seven summer 2018 interns came from intensely selective universities. None attended “Ivy Plus” schools.

Margaret Holt, standards editor for the Tribune, said editors have been putting in efforts to “broaden recruitment.”

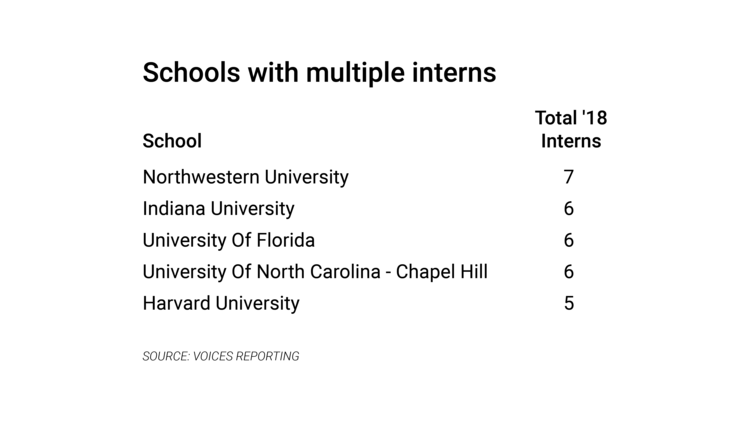

Most popular schools

A handful of schools came up repeatedly as the top feeder colleges for these internships. Among them:

Some of these colleges, such as Arizona State, are not considered intensely selective in general as a four-year college in this analysis, although it is widely considered to have a good journalism program.

The diversity of an intern class can be important in the makeup of the newsroom. We found that at least 29% of the Journal’s summer 2018 interns got full-time jobs, based off on a LinkedIn analysis and a survey filled out by some of that year’s interns.

And when newsrooms aren’t diverse, journalism suffers. Stories are missed, communities are uncovered, scandals unbroken.

U.S. newsrooms have long been overwhelmingly white and unrepresentative of the nation’s increasing diversity.

A lack of diversity among journalists was a central reason why the news media failed in its job reporting on the underlying issues behind riots in the 1960s, the Kerner Commission, a presidential commission, found. Notably, the Los Angeles Times in 1965 had no black reporters when the Watts Riots began, and a black advertising salesman offered to go into the riot zone.

Voices, an independent student-run news project that publishes during the Asian American Journalists Association convention, has found that the leadership of the nation’s largest newspapers were still disproportionately white. Voices has also compared union studies of pay at seven U.S. newsrooms, and found that all of them alleged that men made more than women and that whites made more than people of color.

It’s important that interns be drawn from many parts of American society, said Savannah Eadens, a Columbia College Chicago student originally from central Iowa who interned at the Chicago Tribune last year.

The central Iowa native, who now interns at the Louisville Courier-Journal, said the town she grew up in had a population of 15,000, most of whom voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election.

Her perspective and nuanced understanding of that part of the country could be an asset to mainstream news organizations who overlooked regions of voters in the U.S. during election coverage, Eadens said.

Hiring managers should make an intentional move to hire from other schools, such as smaller, public and community colleges, said Adrienne Shih, an audience engagement intern at the Washington Post last year and a UC Berkeley alumna, and now an audience engagement editor at the Los Angeles Times’ Washington bureau. “It really widens reporting, angles and perspective.”

The idea that the way you’re supposed to go into journalism — through a high-end journalism school — is “basically creating a caste system for young reporters,” Gustavo Arellano, a features writer at the Los Angeles Times and former editor of the OC Weekly, said.

“It discourages you.”

It’s not just The New York Times, he said. Other elite institutions, like his own Los Angeles Times, too often recruit journalists from the same schools and social milieu, he said, making the places a rarefied bubble.

When we spoke with last summer’s interns from the seven news organizations we examined, we asked if they heard about Kim’s tweet; almost all were aware of it.

Orla McCaffrey, a markets intern in the Wall Street Journal summer 2018 intern class, said she went to Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York because she feared the lack of a brand name for her undergraduate school, Binghamton University, would hurt her chances in the industry.

“It feels like we have had to work twice as hard to prove that we are good,” McCaffrey, now a business reporting intern at the Dallas Morning News, said of herself and her undergraduate classmates.

Laura Newberry found herself in a similar predicament when she graduated at the top of her class when she earned her bachelors in journalism at the University of Central Florida. While she was able to get a job post-grad, it was at a smaller paper.

While Newberry said there’s nothing wrong with working at a smaller paper, she felt like attending a more recognizable school would have secured her a position at a bigger paper.

“I would have been able to have skipped a step,” she said, and she would not have gone to grad school.

She took out student loans and earned a master’s in journalism at UC Berkeley, interned at the Los Angeles Times last summer and was subsequently hired full-time as a Metro reporter.

Some journalists familiar with Kim said they were surprised at the tweet.

“Something that he would always tell us during the internship program was — it really didn’t matter what school you went to, it really only mattered about the content that you produce,” said Adriana Lacy, an audience engagement intern at the New York Times last summer.

“It was definitely an uncharacteristic tweet, because we definitely didn’t feel that way when we were interning,” said Lacy, an alumna of Penn State University who is now an audience engagement editor at the Los Angeles Times.

Schools can help give students a boost.

Len Downie Jr., executive editor of the Washington Post between 1991 and 2008, said he got his first foot in the Post newsroom after he was picked by his Ohio State University journalism school administrator, George Kienzle, to shadow journalists there for that summer.

Kienzle had earlier secured an agreement with a Post senior editor for the position. Downie went on to write 13 stories that summer and was later hired. He remembers being the only intern that didn’t attend a school on the East Coast.

Helping Downie, he thought, was his experience and education at Ohio State. The student newspaper, The Lantern, was run like a professional daily newspaper, he said, and many of his journalism professors were working journalists.

But it wasn’t the schools that helped most other students get Post internships back then, he said.

“They weren’t picking them because of the schools, as far as I can tell. I was only an intern — so I’m guessing a lot of this from what I heard — but it seems that it was sons and daughters of friends of the editors, and so the school was secondary,” Downie said.

Downie wasn’t concerned at that time about whether the system of choosing interns was fair.

“I didn’t care. I got to be an intern, I did well, and I got a job,” Downie said. “And then it evolved into a very organized, meritorious, merit-based intern program over the years,” around the time Ben Bradlee became editor and Howard Simon became managing editor.

Today, Downie, professor of journalism at Arizona State and now writing a memoir of his career at the Post, thinks that a school someone attends does matter a little bit.

But when he headed the Post, hiring interns and reporters was not about a school’s reputation, or if someone went to a journalism school.

“What matters is the work,” he said. “You got to submit clips, or you got to submit photos, if you’re looking for a photographer position. And over time you would see that if you selected people based on their work that certain schools might stand out as being the source of a lot of interns.”

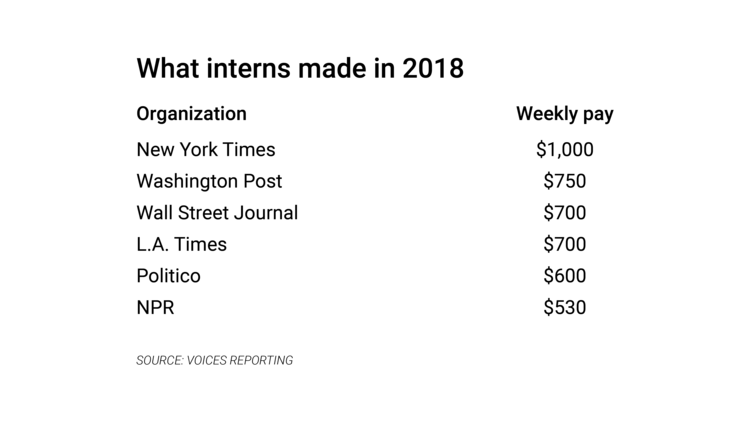

In reporting this story, we also looked at whether a lack of adequate pay proved a barrier to interns. We asked interns for information on what they made, and this is what they told us:

Note: The pay for interns at the Wall Street Journal rose to $900 in 2019.

Among the lower paid interns were NPR, earning $530 a week — nearly half of what the New York Times pays. Nearly all NPR interns who filled out our survey said they either had to dip into their savings during the summer or had to rely on financial help from scholarships or parents. Washington is one of the nation’s most expensive places to live.

For Charlotte Norsworthy, when free housing from a university scholarship unexpectedly ended earlier than her summer internship, she said she had to cut her NPR internship short since she couldn’t afford an Airbnb or hotel room.

Pay at smaller news organizations around the country is often worse.

Caitlin Ostroff still remembers her last week as a general assignment intern at the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. It was the summer of 2016 and her fellow interns had invited her to go out to lunch.

“I burst into tears in front of them because I couldn’t afford to go,” Ostroff, who attended the University of Florida, said in an interview. She only had $100 left in her bank account.

Her internship was unpaid.

Ostroff’s internship last summer at the Wall Street Journal, where she was paid around $700 a week for 10 weeks, was “the most of a living wage” she ever received in her internship career.

Ostroff now works out of the Journal’s London bureau as a markets reporter. She said she is frustrated that in order to “pay your dues” and make it in this industry, interns and early-career journalists often work unpaid or low wage jobs.

“You are already whittling down the pot of who can take these unpaid and low-wage jobs from the start,” Ostroff said. “In most internships at national papers — where you make a living wage — you have to be a junior or senior and have had to have a series of internships before then.”

Mini Racker, an intern last summer for the Los Angeles Times’ Sacramento bureau, said she earned $417 a week over 12 weeks instead of the typical $700 her colleagues made weekly because her internship was funded through, and the pay set by, Stanford University.

To make ends meet, Racker drove for DoorDash sometimes at night during her internship at the Los Angeles Times, and had to get financial help from her dad. Racker is now a digital editor at the National Journal.

Boucher of the Los Angeles Times said she wasn’t aware of the pay Racker received through Stanford until we told her about it. There was no Stanford intern at the Los Angeles Times this summer. Boucher said she thought it was not fair for students coming through that internship to receive less than interns funded directly by the Los Angeles Times.

Stanford University did not respond to our request for comment.

Some journalists say continuing to go back to students from the same schools risks having newsrooms with too many similar journalists.

Randy Hagihara, who recruited interns at the Los Angeles Times from 1999 to 2011, said he wasn’t surprised at our findings. He said he knows a lot of recruiters that establish pipelines at universities familiar to the recruiters.

Publications that solely rely on pipeline schools could be missing out on a wide variety of accomplished students, he said. Hagihara said he tended to select interns from California schools, because of the quality of the students and their proximity to L.A.

One of the best interns he picked in 2003, and later hired, came from the University of Toledo in Ohio, he said. “Up until I read her application, I didn’t even know Toledo had that university,” he said.

“Those are ivory tower institutions and why would they want a person like me?”

— Ashley Powers, freelance journalist and University of Toledo graduate

That young intern was Ashley Powers. At her first summer at the Los Angeles Times, she quickly became known for her features on the Orange County Fair, like about the bizarre contest awarding top prizes to the prettiest of rats (the judging “celebrates the most splendorous of specimens,” she wrote, but “to be a supermodel of the rodent world, a rat also needs rounded ears and smooth color and markings. A lack of temper tantrums helps too.”)

She was hired the following spring, and went on to have a distinguished decade-long stint at the Los Angeles Times, including as Las Vegas bureau chief and spending a year with a team uncovering how the Los Angeles archdiocese mishandled priests accused of abusing children.

Since leaving the Los Angeles Times in 2014, she became a freelance writer, writing for publications like The New Yorker and The New York Times; she is now working on a story for The Washington Post Magazine.

She was a 2017 recipient of New York University’s Reporting Award and is a co-director of the 10-day Princeton University Summer Journalism Program, which seeks to train lower income students and people of color.

At her college, there was no journalism program. No career counselors to help. Her first internship was at the Fostoria Review Times, a tiny paper in Ohio’s farm country, and each summer, she went up to a slightly larger paper. Her senior year, she decided to go for the big papers.

Even then, she said she was too intimidated to apply to papers like The New York Times and The Washington Post because, she remembers thinking at the time, “those are ivory tower institutions and why would they want a person like me?”

Powers said she thought Kim’s tweet was “unfortunate because that single tweet probably discouraged a lot of people from applying to the New York Times internship.” She said she thought that Kim’s “moment of honesty probably had some real consequences and probably really discouraged some people who were applying to internships that they were well qualified for.”

It was only after she arrived at the Los Angeles Times that she understood just how many of her peer interns at that newspaper went to elite colleges, she said. She remembers seeing a list of interns there and feeling very small — a feeling of self-consciousness that she now thinks was imposter syndrome.

“Without Randy scooping me out of nowhere, I don’t know how I would have ended up in a place like the L.A. Times,” Powers told us. “In hindsight, to other recruiters and internship coordinators at elite media organizations, I would have probably been looked at as a risk.

“I only ended up at the L.A. Times because Randy did not see me as a risk,” Powers said. “He saw me as a good prospective job candidate, and that made all the difference.”

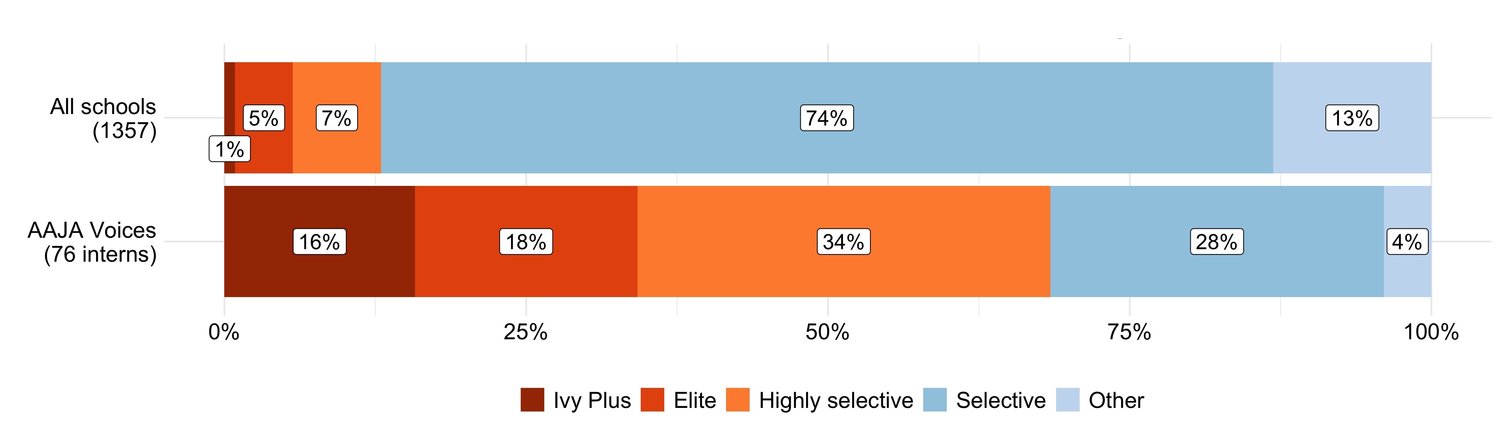

The Voices classes from 2015 to 2019 were also analyzed. Of the 76 students, 68 percent had attended highly selective undergraduate schools. Around one in seven attended an Ivy Plus institution. Among the 2019 class, 75 percent were from highly selective schools out of the 16 students. Three students attended Ivy Plus schools.

Credit: Amanda Zhou

The Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post are supporters of AAJA Voices.

To report on the background of news industry interns, we first created a survey on a Google Form, circulated it on social media, asking current and recent news interns at top major news publications to fill out a form to find out more about whether they got paid, their financial situation during the internship, their race, and their educational background.

We decided to focus on seven major news organizations that ran internship programs during the summer of 2018 — The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, NPR, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune and Politico.

The New York Times and Washington Post’s list of interns for those years were already online. The Los Angeles Times and Politico gave us their list of interns when we asked for them. The Wall Street Journal, NPR and Chicago Tribune declined to provide their intern lists.

For those organizations, we were able to use a combination of internal memos, interviews, LinkedIn searches, survey responses and social media to identify the interns. We also emailed interns we identified and asked them to fill out the survey.

We created a survey to systematically request the interns’ race, if they got paid, their financial situation during the internship, their previous internships,to confirm their schools and if they wanted to be interviewed by us.

The number of interns at each publication varied from six or seven (Politico and the Chicago Tribune) to 33 (NPR). Since the sample sizes for each organization was small, the differences in percentage of interns from intensively selective between organizations should be treated with caution. To give an example, an increase of two interns from intensively selective schools in an intern class could increase the percentage of interns from intensively selective schools by 7%.

After identifying interns, we decided to exclude interns in non-editorial departments, such as the business, marketing and product departments. We included graphic design and social media interns.

To establish the interns’ education background, we tried to send sent surveys directly to more than 150 students through email, Twitter direct messages and other methods. We used LinkedIn searches where we were lacking information on their higher education.

We assembled a list of about 150 interns.

About 70 former interns responded, and we completed follow-up interviews with 16 of them.

After collecting a list of the interns and their school, we needed to systematically rank the selectivity of a particular school. We chose a system already used by a Harvard economics professor, Raj Chetty, which is based off an admissions competitiveness index created by the publication Barron’s, which publishes a popular guide about colleges. The Barron’s index describes how competitive admission is to a certain school. The index takes GPA, SAT scores, acceptance rates and class rank of the school’s incoming students into account.

Chetty’s dataset of colleges and universities was generated originally from the Department of Education’s IPEDS database and College Scorecards database. From this dataset, we excluded two-year or less institutions and for-profit four-year institutions. We found 1,357 schools in the U.S. after excluding these schools.

The same selectivity dataset by Chetty was also used in an Upshot column in The New York Times titled, “Some Colleges Have More Students From the Top 1 Percent Than the Bottom 60. Find Yours.”

Chetty divides school’s selectivity in this way:

“Ivy Plus,” (combining the eight Ivy League schools with Stanford, MIT, Duke and the University of Chicago), which represent the top 1% of the nation’s four-year colleges; schools in this category were rated with Barron’s top selectivity group.

“Elite” universities such as Northwestern and NYU. There are 65 in this category, which represents 5% of the nation’s colleges; These schools also received Barron’s top selectivity rating.

“Highly selective” schools such as UC Berkeley and University of Florida. There are 99 in this category, which represents 7% of the nation’s colleges. This included Barron’s 2nd selectivity group.

“Selective,” schools represent 74% of the nation’s more than 1,300 four-year not-for-profit schools; this included Barron’s 3rd, 4th and 5th selectivity group.

“Nonselective or other,” which represents the remaining 13%. They include newly established schools and colleges that went to too little information. This included Barron’s lowest tiers of selectivity. Other also included schools without enough information to be categorized.

For our analysis, we consider all universities in these three tiers — the top 13% most selective four-year colleges nationally — as “intensely selective.”

See where your school falls in these categories

In our dataset, at least 20 interns had a journalism master’s degree. However, we still only counted their undergraduate degree when determining their school’s selectivity since there was no dataset that described the selectivity of graduate schools, which have a separate admissions process than undergraduate schools.

We used different data to conduct the analysis of the educational background of Voices students. The dataset we had of Voices students is made of a document that generally identifies the school that they obtained their most recent degree, which sometimes were graduate degrees. We used that information for the data analysis, the best available before the publication of this story.

Analysis and graphs were done in the programming language R primarily with the tidyverse package.

New York University

Ohio State University

Emerson College

Dartmouth College

Investigative

Atlanta 2019

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.