criminal justice

After serving lengthy prison sentences and reentering society as adults, members of API Rise recount their experiences in ICE detention and how they were punished a second time for their former crimes.

After serving lengthy prison sentences and reentering society as adults, members of API Rise recount their experiences in ICE detention and how they were punished a second time for their former crimes.

Published August 16, 2025

Malcolm Caminero

Malcolm Caminero

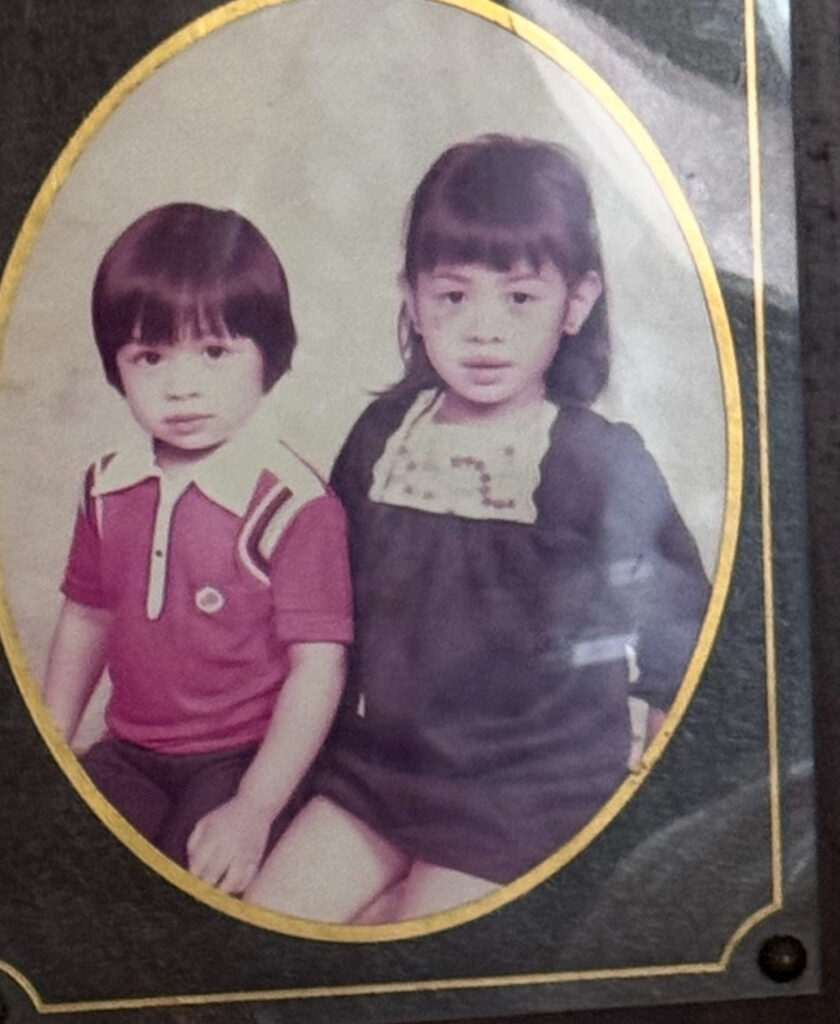

API Rise co-director Billy Taing poses for a photo in the organization’s office in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Malcolm Caminero)

When Billy Taing walked into the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in downtown Los Angeles for his biannual check-in with ICE, he was not expecting to be detained and ordered to be deported back to Cambodia.

Having already spent more than two decades behind bars, Taing was free. But now, he was told that the reason he was being detained by ICE was due to his prior convictions for kidnapping and robbery.

Taing said he was being “criminalized twice.”

He was moved to a detention center in Yuba City, north of Sacramento, where he spent a day and a half shoulder to shoulder with 30 other men inside a holding cell made for 20 people. The odor of pungent, dirty mop water lined the corridor.

With no idea when he would be released, he said he felt “a sense of hopelessness” that he wasn’t going to get out.

“That place is designed for people to give up hope,” said Taing, who spent four months in detention before being released.

Taing described how the monotony of having the same routine day in and day out “wears people down,” adding that he still remembers not being treated like a human being while being in ICE detention.

“All the experience doesn’t go away … it stays with you one way or another,” he said.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration has made nearly 15,000 Southeast Asians targets for detention due to their previous convictions, according to the Asian Law Caucus, the United States’ first Asian American legal and civil rights organization.

To remain in the country, formerly incarcerated immigrants check in monthly at a local ICE office to discuss their case with an officer. However, despite following the rules, there is still a chance they’ll be detained and, in some cases, deported.

Taing said these routine check-ins have become a scary process, knowing that people “could check in and not check back out.”

“While you’re under the deportation process, you can’t realistically have a life, because knowing at any minute … you could be deported,” he said.

In 2018, Taing would serve a second stint in ICE detention — this time for six and a half months. He said in both instances he was released thanks to help from an immigration lawyer.

Unlike prison, those in detention centers do not know when they will be released. In some extreme cases, some people are held for more than a year, which leads some people to make difficult decisions to escape the brutal conditions, he said.

Taing said it was heartbreaking to see others give up hope.

“Just send me to wherever, at least I’m free. I don’t want to be in this situation for any longer,” he said. “So, they willingly just self-deport … they don’t want to fight anymore.”

Just three days away from being deported back home to Cambodia, Taing said he received a pardon from California Governor Jerry Brown, which allowed him to stay in the States.

Taing said he first learned about API Rise during his time in transitional housing, three months after being released.

At the time, there weren’t many programs for the Asian Pacific Islander community and the founders felt they needed to create a space where people could home and feel that they were supported.

The organization supports formerly incarcerated individuals of API descent through monthly workshops, job training and career services to help them better their lives.

He said he remembers attending his first meeting and feeling a sense of belonging and relief that there was a place to talk and share some of the traumatic experiences he went through.

For someone who has been convicted, Billy said there’s a lot of shame associated with that label and being perceived as a “bad immigrant.” He said there was a feeling that nobody in the community wanted to talk about it, especially his family.

Despite having been out of prison for nearly a decade, to the authorities, “I’m just a convicted felon,” he said.

Taing said it was his second stint in ICE detention that helped guide him towards his current work at API Rise. He started as a volunteer and participated in one of their leadership programs, which showed him how important advocacy was.

Now, he serves as the organization’s co-director.

“It’s my passion to serve the community,” he said.

Taing said he feels a responsibility to share his story with others, adding that it is rewarding knowing he is in a position to help others who are going through the same situation as he did.

“I could honestly say I’m lucky that I’m still here … some people are not as fortunate as I am,” he said.

TIN THANG

Tattoos don’t heal all wounds

The buzz of the tattoo gun reverberates off the black and crimson walls of Tin Thang Tattoo Studio, which is covered with large-scale drawings. Each tattoo tells a story. And Thang takes his time inking a new piece over his customer’s old gang tattoo.

“I was 17 years old when I committed my crime,” Tin Thang said. “I was 41 when I was released back to society.”

“You imagine the big gap that I missed. It was a hard adjustment … everything was so fast the first year out because many things had changed,” he said, about having to start his life again in his forties.

As a teenager, Thang joined a gang and later ended up in prison.

When he was finally released, after being incarcerated for more than two decades, he was picked up by ICE and placed in the processing center in Adelanto, California.

Thang said his time in ICE detention was worse because of the intimidation tactics and filthy living conditions. “It was a horrible experience, but I didn’t know yet when I was there,” he said.

For Thang, the one thing that kept him going during his time in detention was a familiar face — his old friend Billy Taing. The two had grown up together and even attended the same high school.

API Rise would help Thang obtain legal representation. They expedited his case to secure his release from ICE detention and provided support to help him get back on his feet.

Since being released from detention, Thang said he has changed his life. Now, he is helping to do the same for others by covering up old gang-related tattoos for those looking for a fresh start.

Thang acknowledges, “I can’t erase my past.”

“I take full responsibility for my poor choices,” he said.

Despite being seven years removed from prison, Thang admits he is still adjusting to the deluge of everyday life, adding that he grew accustomed to the routine in prison — of being told what to do and where to be.

“Some days I just want to be in my tattoo shop and just chill just by myself,” Thang said. “I have responsibilities now. I have to pay my bills.”

Thang said, “I’m just focusing on my small business, my mental health, my physical health, and surrounding myself with family and good friends.”

KANAKA LUNA-JENNINGS

Making the most of second chances

Kanana Luna-Jennings was three years old when her family immigrated to the U.S. from the Philippines in search of a better life. They would eventually settle down in San Francisco.

At 19 years old, Luna-Jennings found herself in trouble with the law and was charged with first-degree attempted murder, robbery, carjacking, and kidnapping. She would spend the next two decades in prison.

In 2018, soon after being released from prison, she was picked up by ICE.

Luna-Jennings said she spent time at the ICE detention center in San Bernardino before being transferred to Adelanto a few days later. It was there that things got worse.

She said women were routinely fondled during patdowns, were forced to shower with the door open in plain view of male officers, and were provided a limited amount of feminine hygiene products.

But she didn’t let her time in detention break her spirit. Since being released from detention, Luna-Jennings channeled the emotional, mental, and physical pain she felt into action.

Luna-Jennings, 49, works as a counselor with API Rise, where she preaches the values of kindness, integrity and accountability.

As part of her job, she oversees programs that teach youth how to use their voice to become community leaders, prevent them from getting into drugs or gangs and encourage them to pursue higher education.

Luna-Jennings said she discovered that her true purpose was helping people who find themselves in similar positions to the one she was in.

For those who are struggling, she stressed that “there is support out there, and don’t be ashamed to ask for help.”

“I used to always think if I could change my life and do it all over again, I would do this differently, I would do that differently, but reflecting on my life now, I wouldn’t change anything,” she said.

She said her experiences shaped her into the person she is today and is thankful for the challenges she’s had to overcome.

“I’m very remorseful for what I’ve done, and that’s why I continue to do what I do, to be of service to a community in honor of the people that I’ve ever hurt,” Luna-Jennings said.

“I always want to leave a legacy that I helped people, and I didn’t just feel sorry for myself.”

University of Southern California

Seattle 2025

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.