Education

The estate of Dr. Jane Wu, a Chinese American neuroscientist who died by suicide after an investigation by the National Institutes of Health, has filed a lawsuit against Northwestern University alleging discrimination.

The estate of Dr. Jane Wu, a Chinese American neuroscientist who died by suicide after an investigation by the National Institutes of Health, has filed a lawsuit against Northwestern University alleging discrimination.

Published August 18, 2025

William Tong

William Tong

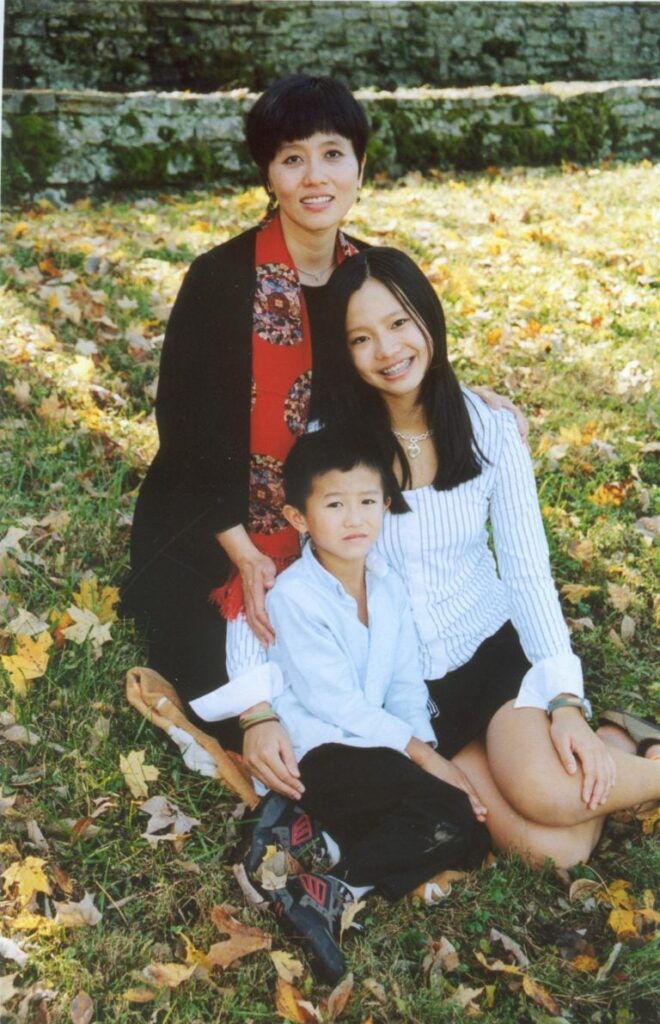

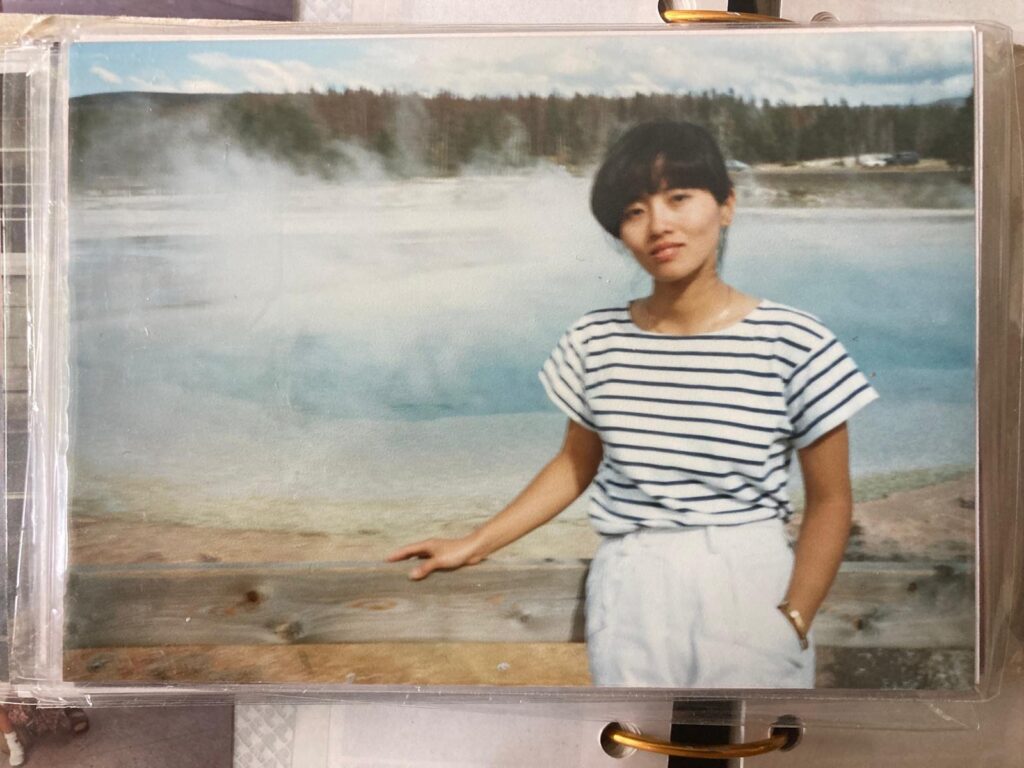

Image of Professor Jane Wu. (Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Rao.)

Content Warning: this article contains mentions of suicide.

Professor Jane Wu had less than a month to submit her first grant application in years to the National Institutes of Health. Wu, who worked at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, had obtained approval to apply from school administrators by the first week of May 2024.

Days later, medical school officials shut down Wu’s lab in its entirety, effectively eliminating “any chance for Dr. Wu to resume her funded research,” according to a legal complaint against Northwestern University (NU) filed by Wu’s family in June 2025 — almost a year after her death.

“It was a very, very sad tale of an outstanding scientist and wonderful human being who got caught up in the politics of the day between the United States and China — and suffered devastating losses,” said Professor John Kessler, Wu’s colleague and former chair of the medical school’s neurology department.

But this wasn’t the first blow to Wu’s research.

Between 2019 and 2023, the NIH investigated Wu, a neurology professor, based on her Chinese affiliations, according to the complaint. Northwestern, at the NIH’s direction, took steps that prevented Wu from taking part in her research during that time, the complaint alleges. When the NIH eventually ended its probe and she was allowed to resume her research, she had already lost resources and staff.

The university revoked the last of her lab space in May 2024, according to the legal complaint, which argues Northwestern discriminated against Wu based on national origin, gender and disability status.

Wu’s story has contributed to a “chilling effect” on students, faculty and staff looking to pursue research at the university, some scholars have said. It parallels wider fear surrounding the federal government targeting researchers with Chinese connections amid rising tensions between the U.S. and China and a changing academic landscape.

The lawyer for Wu’s estate, Thomas Geoghegan, said Wu’s “rights were violated, and we intend to seek redress.” He would not comment specifically on the complaint or on questions of law.

“A great injustice was done to my mom,” Wu’s daughter, Elizabeth Rao, wrote to The Daily Northwestern (also known as The Daily). “My mom’s death is a tragic loss for our family, for the Asian American community, and for American science.”

‘Family and career, hand in hand’

Born in Anhui, a mountainous province in central China, Wu graduated from Shanghai Medical University in 1986.

She came to the U.S. during August of that year to embark on a Ph.D. in cancer biology at Stanford University. Wu presented her dissertation on the molecular biology of Hepatitis B in May 1991.

Wu built a family as she rose through academia, Rao wrote to The Daily. Wu’s husband at the time, Yi Rao, also researched biology and taught at Northwestern until 2007.

“That was mom in a nutshell: family and career, hand in hand,” Elizabeth Rao wrote.

Throughout her childhood, Rao recalled, Wu made sure Rao and her younger brother could experience the “quintessential American childhood,” through sports, dance classes, choir and road trips.

All the while, Wu worked on her research full time. She continued to build her lab, and would invite colleagues to family celebrations, Rao added.

“I miss her handmade dumplings, and our shared Thanksgiving dinners with her lab members,” Rao wrote.

After finishing her doctorate, Wu conducted postdoctoral research at Harvard University. She then served on the faculty of Washington University in St. Louis and Vanderbilt University, before moving to Northwestern in 2005.

Chief among Wu’s discoveries was how certain genes associated with ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases could directly damage the mitochondria — the parts of cells that generate usable energy. Although much of her research centered around neurodegenerative diseases, she also studied other topics, including genetic links to lung cancer.

Before the NIH investigated her, Wu was examining how protein involved in neurodegeneration also affected cancer’s movement to different parts of the body. During her time at Northwestern, Wu’s research received more than $10 million in NIH grant funding.

While many scientists with Wu’s level of seniority take on oversight roles and spend less time in the lab, Wu remained “close to the bench,” Rao wrote, eager to perform experiments herself.

“I think she wanted to stay close to the methods,” Kessler said. “So she could think about how she could change them and change the field.”

A different time

By 2010, Wu was collaborating with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Biophysics Institute, a research group based in Beijing. At the time, the Feinberg dean’s office said the partnership was “fine,” Kessler said.

But research collaboration had changed when the NIH opened its investigation into Wu in 2019. The federal government was developing a more “antagonistic view toward scientific collaboration with China,” Kessler said.

The NIH and Northwestern scrutinized Wu for about four years, according to the legal complaint. Wu’s former lawyer, Peter Zeidenberg, said the government investigated her to see whether she “properly disclosed … certain affiliations with China.” Zeidenberg said he didn’t feel Wu “did anything wrong.”

Kessler said Wu was temporarily banned from NIH-sponsored research during the investigation. As a result, Wu’s “very strong research effort” was “completely thrown off its track,” Kessler said. She remained on Northwestern’s payroll as a faculty member.

Northwestern President Michael Schill told The Daily that he didn’t know of any particular examples since 2020 of the university cooperating with federal officials to investigate compliance with grant application and disclosure rules. If there were, the university would comply with them, Schill said.

Kessler and another one of Wu’s colleagues, Robert Vassar, received two of her grants that were reassigned during the investigation. Kessler and Vassar had also supervised members of her lab group, according to Kessler.

Throughout the process, Wu talked about feeling a sense of hopelessness, Kessler recounted.

“Because science and research are … an extremely important part of my life, having been ordered not to participate in any of our major research projects is a tremendous torture and stress to me,” Wu wrote in a letter during the investigation, according to the complaint.

‘A lifetime of work’

The NIH ended its investigation by December 2023, according to the legal complaint. The agency did not find any wrongdoing on Wu’s part. Still, the investigation had derailed her research.

In January 2024, Northwestern began to cut Wu’s pay due to having “research inactive” status, according to the lawsuit. One of the grants she originally won remained reassigned to Vassar, her colleague, the complaint continued.

In February 2024, administrators shut down part of Wu’s lab space. They also moved and put away many of Wu’s lab materials, which the complaint alleged “inflicted severe emotional distress upon Dr. Wu, as it threatened the value of a lifetime of work and hindered her from applying for new funded research.”

Nevertheless, she aimed to meet the NIH’s June 2024 grant application deadline, according to the complaint. Wu emailed her department chair, Professor Dimitri Krainc, about her goal on May 1, 2024.

“This looks good,” Krainc emailed back, according to the complaint.

He emailed Wu the next day that Dr. Michael Lauer, then-director of the NIH’s Office of Extramural Research, had said: “We understand that Dr. Wu is now in good standing at NU and therefore eligible to be designated by NU as key personnel on projects.”

Lauer did not respond to interview requests.

Krainc announced a few days later that Feinberg was shutting down the rest of Wu’s lab space, according to the lawsuit. Feinberg Dean Eric Neilson confirmed the decision to Wu on May 13. She emailed Neilson requesting that the lab space remain open until she had the opportunity to submit the grant application, according to the complaint.

“Although my team is small, we are working hard and making good progress,” Wu wrote.

Neilson did not respond to the email, according to the complaint.

Kessler noted that physical lab space was generally in high demand. He said the lab shutdown was “somewhat cruel,” but added that it’s unclear whether the decision was “cruel in intent.”

“After her family, she viewed science and her scientific efforts as being the absolute most important thing and the thing that described her persona,” Kessler said. “So taking this away from her was really devastating.”

Handcuffed and hospitalized

Northwestern University Police, Chicago Police Department, and Chicago Fire Department personnel arrived at Wu’s office on May 23, 2024, after a call from the medical school, according to the complaint. Chicago Office of Public Safety Administration records show the agencies responded to one mental disturbance call that day on the block containing Wu’s lab.

University and city police handcuffed Wu, causing “serious bruises on her hands and wrists,” the complaint continued. She was then taken, in Krainc’s presence according to the lawsuit, to Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s emergency room, less than half a mile away. She was given the option to admit herself to Northwestern’s psychiatric center or be admitted involuntarily by NU and Krainc, which could require a court order for her to gain release, according to the complaint.

She chose the former.

In an August 2025 email statement to The Daily, Krainc denied allegations in the complaint that he had announced the closure of Wu’s lab. He also said he was not present when she was handcuffed and had “absolutely nothing to do with her admission to the hospital.”

Administrators did not “officially” reach out to family members, according to the complaint. A Northwestern Medicine spokesperson did not answer questions about Northwestern’s involuntary admissions policies.

For about two weeks, Wu stayed in the psychiatric center. She hadn’t been allowed access to any electronic devices during her time at the center, according to the complaint. Wu left the psychiatric center on June 6, 2024. She did not submit her grant application.

Northwestern spokespeople said the university denies the lawsuit’s allegations and will “respond to the complaint in the appropriate forum at the appropriate time.” They declined to provide more details. NBC News has reported that the school plans to file a motion to dismiss the case, though spokespeople did not confirm whether that is its plan.

‘A person with strong will’

Wu died by suicide at her home in Chicago on July 10, 2024. She was 60 years old.

Her former lab sat empty for months, with a stack of envelopes building up inside the mailbox by October. Northwestern did not publish a formal announcement or obituary about her death.

The university’s standard practice is to not publish obituaries “except in the case of leadership or distinguished faculty” and to take down websites and close laboratories, Neilson wrote in an email obtained by The Daily to a faculty member who had asked about Wu’s death.

Neilson had also told that faculty member, “We do know that she died at home after a brief illness.” Earlier in August 2024, the South China Morning Post had reported that Wu’s death was by suicide, and the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office also ruled her death as such.

Kessler said Wu “faced a lot of adversity in life,” but overcame those challenges. She described one of those struggles in her 1991 Ph.D. dissertation.

“When both of my parents were sent to a labor camp and separated from me, my grandmother … set a good example for me to be a person with strong will, never bent over to any difficulty or frustration,” Wu wrote.

Rao described her mom, who was also a cancer survivor, as “resilient” and a “gentle soul,” agreeing with Kessler about Wu’s passion for science.

“For her, being a research scientist was not just a job but her life calling,” Rao wrote. “She dedicated her life to working for the greater good.”

And to the researchers Wu mentored, like University of Texas San Antonio professor Margaret Flanagan, Wu’s intense devotion to research was balanced with “an innate generosity,” the younger professor wrote to The Daily.

“I always stand by my own principles and core values,” Flanagan recalled Wu saying frequently. “Helping others gives me endless joy.”

If you or someone you know may be thinking of suicide or is in crisis, contact the 988 national suicide hotline.

Northwestern University

Education

Seattle 2025

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.