Religion and belief

At a time when churches are shuttering, some are opening their doors wider than ever, facilitating refugee resettlement. But in so doing, faith-based organizations are stepping into a landscape rife with pitfalls.

At a time when churches are shuttering, some are opening their doors wider than ever, facilitating refugee resettlement. But in so doing, faith-based organizations are stepping into a landscape rife with pitfalls.

Published August 29, 2025

Kabir Burman

Kabir Burman

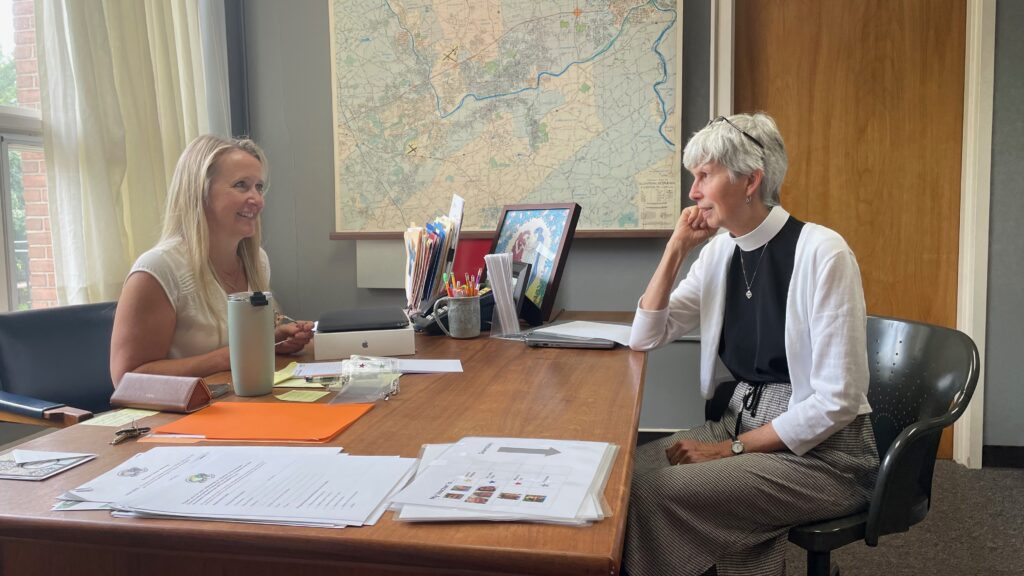

Rev. Maria Tjeltveit and Jessica Entwistle walk through the pews of the Church of the Mediator in Allentown, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Kabir Burman.)

In the heart of Allentown, Pennsylvania, tucked between row houses and aging sidewalks, stands an Episcopal church — a modest parish with stone walls, stained glass, and a quiet evolution unfolding inside as the nation outside wrestles with what it means to be a country of immigrants.

The path to legally entering the United States has grown more daunting since the Church of the Mediator was consecrated in 1905. Family-based visas and refugee resettlement are being constrained by new executive actions and legal hurdles, while policies like travel bans and reports of “anti-American” ideological vetting complicate a system that can seem confusing to many.

The result: record backlogs, chaos and confusion — trends that deepen uncertainty for those seeking safety or a fresh start and draw concern from faith leaders like Rev. Maria Tjeltveit. The church’s retired rector and the founder of the Refugee Community Center (RCC) — a nonprofit entity housed in the church — never imagined her call to ministry would lead her here. Born in Japan to American Episcopal missionaries and raised there until the age of eleven, she remembers vividly the feeling of being a stranger. “When I moved to America, this was supposed to be my home, but it was a foreign land to me in many ways. That shaped who I am as a person and as a priest,” she said.

That sense of feeling like an outsider now gives her empathy for the refugees who have come to call Allentown home — and it’s also what drives the church’s evolving role as a refuge for immigrants.

Church and state

Faith communities have historically been central to both progressive and conservative movements in the United States — from Black churches at the forefront of the Civil Rights era to the rise of the Religious Right in the 1980s.

In more recent years, the American Evangelical movement has been closely associated with conservative policies like opposition to abortion and Christian nationalism; other groups like the Episcopal Church and Catholic Bishops have taken strong public stances in support of immigrants and refugees.

Evangelicals themselves appear to be split over recent immigration policies. According to a recent survey, nine in ten evangelicals support immigration legislation that would “ensure secure national borders.” Yet the same proportion also believes any potential legislation and laws should “protect the unity of the immediate family” and “respect the God-given dignity of each person.”

“Most of the work done with refugees is through faith-based communities,” said Jessica Entwistle, director of the RCC. “World Relief is evangelical. Global Refuge is Lutheran. Our work is rooted in the Episcopal tradition.”

Pope Francis made headlines for criticizing immigration stances, including those promoted by U.S. political figures like Vice President J.D. Vance. These tensions are not just playing out in Washington; they are reflected in small towns across America like Allentown, where churches become the frontline of welcoming — or resisting — new refugees.

Far from the national spotlight, churches like Mediator are practicing a theology of welcome. But these faith-based organizations are also subject to pitfalls, navigating spaces that have become increasingly politicized.

A community transformed

The story of Mediator is one of institutional evolution. Across the United States, church attendance is declining. Congregations are shrinking, pews are emptier, and many houses of worship are shuttering altogether.

Gallup surveys highlight a historical decline in both weekly attendance and formal membership, forcing many congregations to close their doors or consolidate with others. For those that remain, survival often depends on finding new ways to serve.

Mediator, like many mainline churches across the country, had seen its congregation shrink over the years. Sunday attendance was down, younger families weren’t returning, and longtime members were aging, according to Tjeltveit.

This attendance and participation crisis led Tjeltveit towards a new perspective. “We realized we were asking the wrong question. It wasn’t about how to get more people in the pews or money in the coffers. The real question was: What is God up to in our neighborhood, and how can we get involved?”

“And I think that when you focus on that mission and that sense of call and that connection to the community, then God provides in a way that you discover new things, and it can attract new people to your congregation.”

It was during a spring 2016 meeting of the Interfaith Action Committee of the Lehigh Conference of Churches that Rev. Tjeltveit first heard an idea that would change everything.

The committee — made up of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish clergy, and non-clergy members — had been meeting regularly as the Syrian civil war created a surge of refugees. Many were resettling in Allentown, drawn to its well-established Syrian community.

Just a few months earlier, in November 2015, then-Allentown Mayor Ed Pawlowski had spoken out publicly in support of welcoming Syrian refugees. His remarks sparked this large interfaith gathering of support, and the issue of resettlement remained a central topic.

For Tjeltveit, it was a moment of clarity. “I feel like God just gave us the answer.”

A new chapter

From that seed, a new purpose grew and Mediator, by way of the RCC, now serves “as a place for arrivals to connect and feel welcome and feel like they belong,” said Entwistle.

The very building of the church tells a story of displacement and resilience. Refugees have not only walked through the doors of Mediator — they’ve left their mark in the glass, the wood, and the wine.

The stained glass above the altar that illuminates the church today was itself crafted by a Latvian refugee. In the 1950s, a Polish couple — themselves refugees — joined the congregation. The husband made wine, which the church later used for communion. In the 1980s, one of Mediator’s priests was a refugee from Uganda. Today, the Joel Nafuma Refugee Center in Rome bears his name.

Reflecting on this past, Tjeltveit noted that “our history has actually prepared us for this, even if we hadn’t been paying attention.”

Now, on any given weekday, the once-empty basement of the church hums with activity: toddlers scribbling with crayons during childcare sessions, volunteers helping students fill out job applications, and instructors walking students through the difference between “should” and “could” in English language classes.

Volunteers like Catherine Hoffman, a resident of Allentown, have become part of that rhythm. “I like the people. They’re interesting — from all different countries — and the volunteers are lovely,” she said. “It’s so moving that someone has to leave their country for terrible reasons: violence, hunger, instability. I just talked to someone today, a young woman who had to leave her children in a different country and feels very bad about it.”

Just last month, RCC hosted a celebration for World Refugee Day with refugees and volunteers alike gathering over dishes from Afghanistan, Sudan, Syria, and Venezuela, lined up on fold-out tables. Attendees got henna tattoos while listening to the lively beats of the Bachata, Indian classical dances, and Christian opera/rock.

But even in a place defined by welcome, building community across lines of faith, culture, and trauma comes with its challenges.

The challenges of building community

Faith, persecution, and language can all be flashpoints — especially for refugees who find themselves in a foreign country, speaking a different language.

Tensions between refugees and the communities in which they have resettled are a topic of heated political debate. The debate has raised deeper questions about who gets to belong in spaces built on compassion; the role of religious institutions in resettlement; and the cultural and political limitations of these faith-based groups.

At the national level, the Episcopal Migration Ministries (EMM), the denomination’s resettlement arm, recently made headlines for refusing to resettle Afrikaners from South Africa — primarily white individuals seeking asylum.

Their reasoning, Entwistle explained, had less to do with race and more about definitions. While the current U.S. administration calls white South Africans refugees, “Afrikaners are not refugees as defined by the UN.”

“We really haven’t had much issue with our [refugee] population mistreating one another,” Entwistle said. “There was a little bit of racism. People not wanting to be in class with different kinds of people.”

Her team made their stance clear: “If you can’t be in class with other people, then you can’t be here.”

Nevertheless, Entwistle believes that shared experiences often open doors to empathy. “A lot of the people we’ve resettled, because of the trauma they’ve witnessed firsthand, have more compassion and mercy,” she said. “I’m impressed with the amount of mutual respect and compassion people can have for each other, even though they’re coming from warring tribes in some situations.”

“If you can start the conversation about what it feels like to be in a new country and not speak the language, then you can start to have a little bit of compassion for each other, even if — going back to your country of origin — your people are in conflict,” Entwistle explained. “It takes a lot of grace on both sides, really.”

Faith as action

For Entwistle, this service isn’t just an extension of her belief — it’s her belief in motion.

Faith, she argues, is not confined to prayer or scripture alone. “Because of what I believe about God, I can’t be selfish,” she says. “When I read Jesus’ words, and the things he said about loving the stranger … I think it’s integral to the practice of my faith.”

Entwistle, as a member of an evangelical community, is deeply attuned to how Christianity is perceived in today’s political climate. “These days, ‘evangelical’ feels like a dirty word,” she said. “I like to say I’m a Jesus follower.”

Though she acknowledges that the evangelical movement has “done some beautiful things,” Entwistle is candid about her discomfort with the current mix of religion with wider political movements, as well as her own evolution in serving refugees.

“I’ve learned how small I am … how big God is and it’s helped me surrender some of my arrogance,” she reflected.

Still, she wrestles with the tension: how to stay faithful in a system where politics often harms the vulnerable. “When politics is abusing people — how do you speak up?”

She decided to refer to herself as a “Jesus follower,” a conscious effort to separate spiritual conviction from institutional identity — rooted in a desire to reclaim the compassion and clarity she believes her faith demands.

Many faith-based institutions, like World Relief, HIAS (formerly Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), and even the Episcopal Migration Ministries (EMM), are non-proselytizing in that they refrain from actively attempting to convert others to their religion.

While federal rules have prohibited the use of public funds for religious activities, including proselytizing, many organizations take it a step further. For instance, World Relief’s volunteer handbook explicitly states, “we strongly discourage any form of proselytizing (attempting to coerce or convert someone to your religion).” Others, like HIAS, describe their mission as serving refugees “regardless of their national, ethnic, or religious background.”

Entwistle has found that this decision “has sometimes limited who is willing to volunteer with us, [but] it has not limited who we are able to serve.”

The way forward

Faith-based organizations can provide the first anchor for refugees in this country, offering strength, community and a sense of belonging in the face of upheaval. But relying on religious institutions alone has its limits.

Past resettlement efforts show the risks when sponsors misunderstand or override cultural and religious practices; well-intentioned support can veer into misplacement and harm. Advocates and caseworkers say the most durable outcomes come when faith partners are integrated with public services and community organizations.

In cities across the U.S., churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, and other worship spaces provide services ranging from language classes to legal clinics, meals and shelter. From Texas border towns to Midwest suburbs, Northeastern cities to the RCC in Allentown, religious institutions are serving as first responders in the work of immigrant integration.

Together, these institutions reveal a quiet yet powerful story: while the national immigration debate often fractures along partisan lines, communities of faith are reimagining their mission through welcome — reshaping not only the futures of newcomers, but also the future of American faith itself.

Muhlenberg College

Seattle 2025

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.