Student work • Washington, D.C. 2023

Many Asian Americans believe gun laws need to be stricter but are losing faith that lawmakers will take sufficient action to stem the violence. Some are turning their focus instead to mental health care as a way of preventing gun violence and mitigating its long-term impacts.

Many Asian Americans believe gun laws need to be stricter but are losing faith that lawmakers will take sufficient action to stem the violence. Some are turning their focus instead to mental health care as a way of preventing gun violence and mitigating its long-term impacts.

Published July 21, 2023

Kaushiki Roy

Kaushiki Roy

Annie Li

Annie Li

Two years after the 2021 Atlanta shootings, Ya Wa Spa has replaced the former Gold Spa, where three women were killed in 2021. Photo courtesy of Eddy Chiao

Storystream

Read more from this series.

Nineteen-year-old Ravi Parekh was preparing for his 11 a.m. class when he received the call that his best friend and roommate had died.

He later learned that Farhan Towhid, along with Towhid’s older brother, had killed their parents, grandmother, and twin sister, before dying by suicide themselves.

“It was earth-shattering for all of us because we were so close to the situation,” Parekh said.

Towhid demonstrated signs of extreme mental illness months before he killed himself and his family, including threatening to take the lives of his roommates, Parekh said.

Towhid’s murder-suicide is one of many instances of gun-related deaths in the Asian American community. Roughly 650 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders die by gun-related violence each year, with the majority being suicides, according to the Giffords Law Center. While Asian Americans experience a lower gun violence rate than other ethnic groups, those numbers are rising — from 2016 to 2020, AAPI gun deaths increased by 10%.

While many Asian Americans believe gun laws need to be stricter, some are losing faith that lawmakers will take sufficient action to stem the violence. Many are instead turning their focus to mental health care as a way of preventing gun violence and mitigating its long-term consequences.

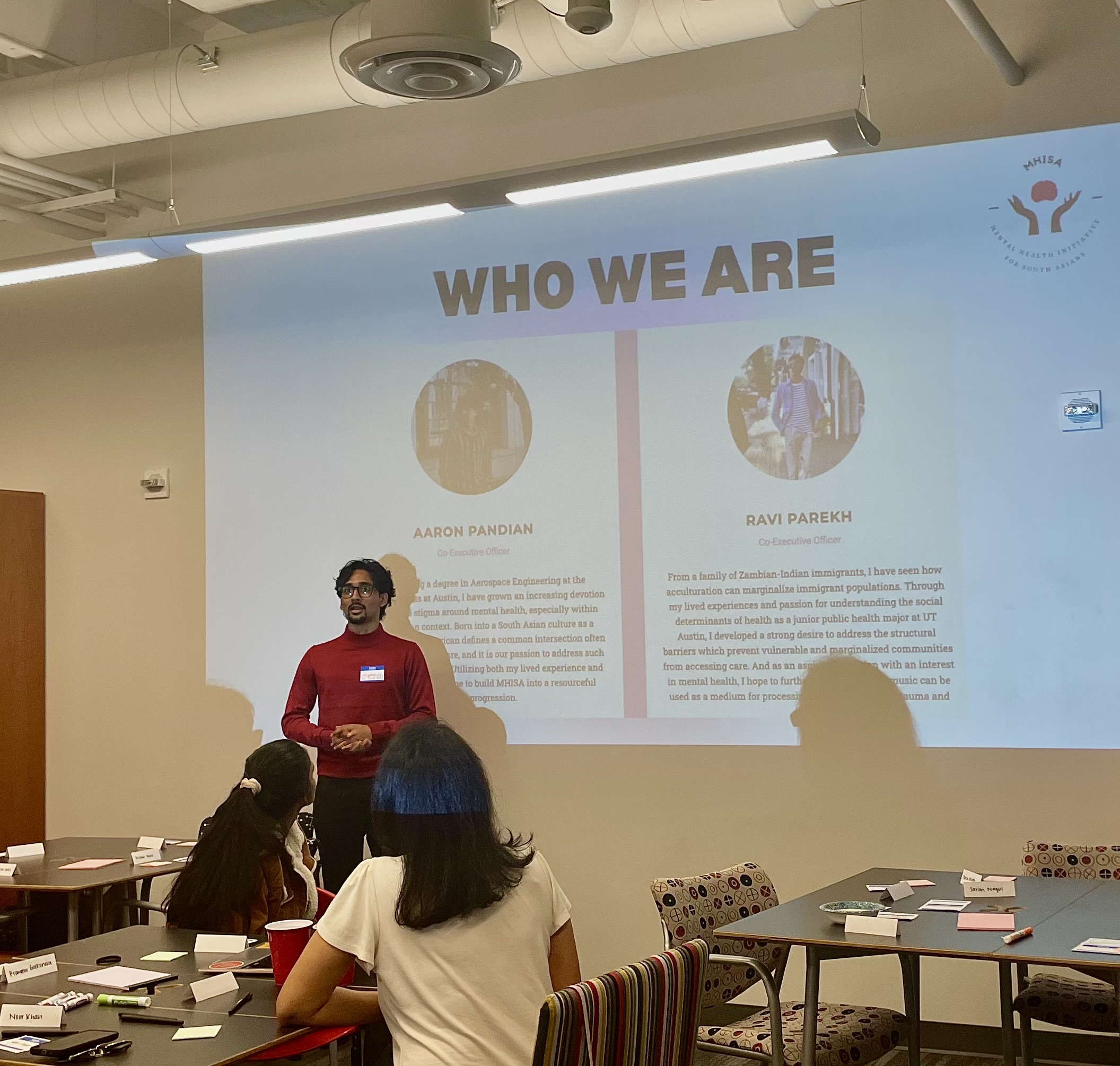

Parekh co-founded the nonprofit Mental Health Initiative for South Asians (MHISA) to provide mental health support and resources for his community. The now senior at the University of Texas at Austin said co-founding MHISA helped him cope with the loss and trauma he experienced after his friend’s death.

Ravi Parekh co-founded the Mental Health Initiative for South Asians after his friend’s suicide. Photo courtesy of Alishba Javaid.

“[Towhid’s parents] were already well aware of his mental health issues,” Parekh said. “But I guess it was an unfortunate combination of a lack of knowledge and awareness as well as the South Asian immigrant perspective that you can persevere through anything [that led to this outcome].”

For Lily Trieu, the founder and executive director of Asian Texans for Justice, working with policymakers to address mental illness in the Asian American community is a top priority going into the 2024 elections. Specifically, her team hopes to expand mental health care in public education.

“Mental health resources and access is already underinvested,” Trieu said. “For AAPI communities where there is such a stigma in talking about mental health and seeking out mental health … a lot of young people’s public education system is kind of their best shot at getting mental health care.”

On top of the mental health crisis in Asian American communities, Trieu said anti-Asian rhetoric and a lack of accountability from lawmakers also contribute to the increase in gun violence.

“What a lot of folks in power don’t understand is when they make comments like ‘China’s the enemy’ or ‘we can’t trust Chinese people,’ while they’re not necessarily talking about Asian Americans, they’re perpetuating this idea that people who look Chinese or who look Asian are a threat to America,” Trieu said. “They’re creating a more volatile environment … where AAPI’s already don’t feel safe.”

Asian Americans felt that volatility after a series of Atlanta spa shootings in 2021 left eight people dead — six of them Asian women. Jane Wang, then a junior at Emory University, lived just three miles away from two of the spas. She expressed her anxiety, fear, and frustration after the shooting.

Two of the three spas where the 2021 Atlanta shootings took place were on Piedmont Road. Photo courtesy of Eddy Chiao.

“How do I talk to … people who don’t want to or need to think about race, all while hoping that someone doesn’t shoot me along the way for the crime of being Asian?” Wang wrote in an op-ed published days after the tragedy.

Some Asian Americans who now fear for their lives are purchasing their own firearms to stay safe. From 2020 to 2021, 27% of gun retailers reported an increase in Asian American buyers, according to a National Shooting Sports Foundation Firearm survey.

Phyllis Myung, who lost friends in a mass shooting at an Allen, Texas shopping mall in May, said she understands why some Asian Americans are buying firearms for protection but believes more guns will ultimately contribute to more violence.

Cindy and Kyu Cho and their two children attended Myung’s church in Boston before they moved to Texas to be closer to family. The couple and their three-year-old son James were among the victims of the attack on an Allen outlet mall, leaving their six-year-old son as the family’s sole survivor. Because Asians make up the second highest racial demographic in Allen, and four of the shooting’s eight victims were of Asian descent, some Asian American advocacy groups are concerned the community was deliberately targeted in the shooting.

“We don’t feel safe anymore,” Myung said. “It can happen anywhere and to anyone now.”

Wang also noted the increased frequency of mass shootings in recent years with Asian American victims. “Each time, it hits a little harder. And then you start to notice it becoming normalized. That also hits in a different way.”

Wang said she is losing faith in authorities’ ability to enact change relating to gun violence because there are numerous policy issues drawing their attention.

“Gun violence is obviously going to be one of the things that I would consider very highly when deciding who to vote for,” she said. “At the same time, I’m very aware politicians know there’s a thousand different issues nowadays that can pull at all of our attention. And when that happens, it also becomes easier for them to not have as much accountability.”

Without seeing their concerns about increased gun violence addressed by lawmakers, some Asian Americans like Parekh have taken matters into their own hands to promote mental health care among their community.

Parekh, who originally founded MHISA to combat increased gun violence, now focuses primarily on promoting mental health care. He said finding a way to alleviate the stigma surrounding mental illness can help reduce gun-related deaths within the community.

He is currently creating an online database for MHISA where South Asians can find mental healthcare providers. He hopes the organization will help South Asians struggling with mental illness feel a sense of support from their community.

“Without their own families supporting them, [mental illness] can exacerbate feelings of loneliness and social isolation,” Parekh said. “So helping that person understand that they aren’t alone is a very important thing to do.”

Editor’s note: If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, dial or text 988 or visit 988lifeline.org.

Kaushiki Roy is a rising senior at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently working as a freelance reporter for the Austin American-Statesman. She has primarily produced print stories and wants to work in the East Coast after graduation.

Annie Li is a writer and graduate student at the University of Oxford, studying the history of religion and activism in Asian American communities.

Washington, D.C. 2023

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.