Feature

Student work • Washington, D.C. 2023

Validation only comes after years of coping with ADHD symptoms and frayed relationships with parents

Validation only comes after years of coping with ADHD symptoms and frayed relationships with parents

Published July 22, 2023

Nollyanne Delacruz

Nollyanne Delacruz

Macy Castañeda Lee

Macy Castañeda Lee

Javon Roman Huynh

Javon Roman Huynh

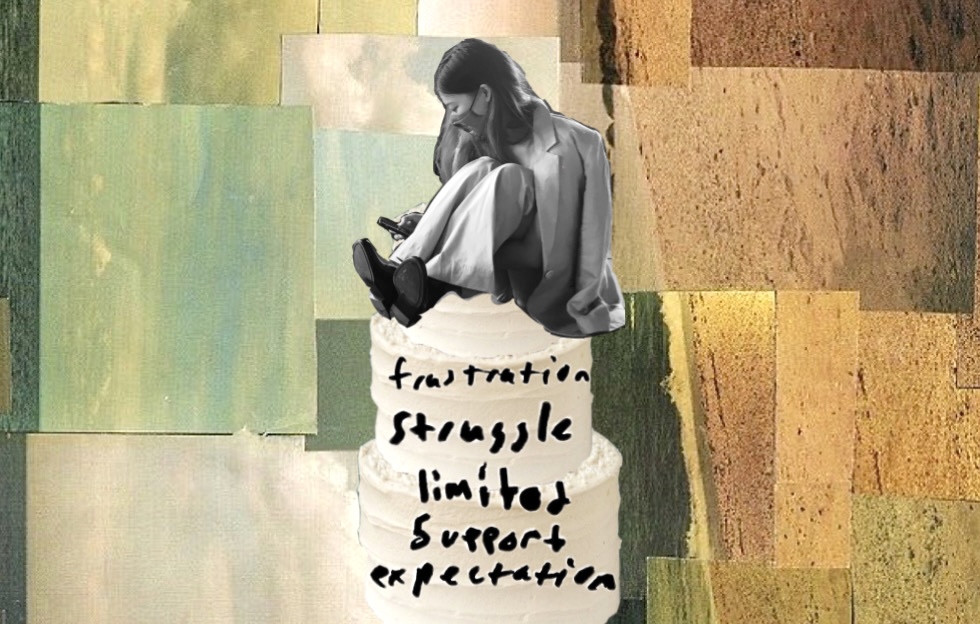

Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Jamie Jiang, one of our interviewees, with her sister during their childhood. Art clipping courtesy of Pinterest, re Emma Klee & Prudence Dudan.

When Jamie Jiang received her first diagnosis for attention deficit hyperactive disorder as a seven-year-old in Shanghai, China, she decided to treat herself through sheer willpower. She forced herself to stop having outbursts at school and strained to pay attention to class lessons, assuming the disorder would go away one day.

“I just thought that there was something funny about me that meant I couldn’t do basic things in academics and always had to take the consequences,” Jiang said. “But then I had to kind of push through somehow and figure out what I could get good grades in.”

But a decade later, her counselor at a Massachusetts high school told her ADHD doesn’t go away. She began connecting the dots in her mind: the persisting attention problems, academics always being challenging and never being able to stay in one place.

Jiang’s experience isn’t unusual for Asian Americans with ADHD. AAJA Voices spoke with several Asian American adults with ADHD, who all spoke of symptoms they experienced since childhood, only to be validated much later in adulthood. All spoke about how their parents could not piece together erratic childhood behavior. The result: a frayed relationship with their parents built around their ADHD symptoms.

Jamie Jiang at childhood. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Getty Images & thevxlley.

The conversation with her counselor illuminated so much for Jiang. She went off to research the condition. Four years later, she finally obtained an ADHD diagnosis in the U.S. during her final year of college.

As ADHD has gained considerable attention on social media in recent years, several peer-reviewed academic studies have also corroborated a considerable increase in ADHD diagnoses in America. One 2018 study that examined data on low-income patients on Medicaid found that ADHD prevalence among adults increased fivefold from 1999 to 2010.

Megan Miller, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who studies the driving factors that cause autism and ADHD, said she has come across lots of misconceptions about mental disorders, including some Asian patients and their parents who think ADHD is something kids or adults can simply control without appropriate treatment.

“ADHD exists across cultures… There are differences with how it is interpreted and how stigmatized it may be,” Miller said. “For AAPI families, generational aspects are a big part of it.”

While research on Asian American adults with ADHD is sparse, the body of work on Asian children with ADHD is larger — and much of it points to considerable disparities in childhood diagnoses. Researchers point to the model minority myth producing misconceptions about the likelihood of Asian Americans having a mental health illness or disorder, and it’s related to parents misunderstanding their kids’ ADHD symptoms.

One 2004 study found Asian children have the lowest odds of getting diagnosed with ADHD and are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and adjustment disorders. A 2022 study found Asian children have the lowest odds of receiving medication treatment for ADHD after diagnosis.

Photos & edit by Macy Castañeda Lee

Nandini Jhawar, a graduate student researcher at Syracuse University, said many factors contribute to these disparities.

“Mistrust of predominantly White healthcare systems, lack of culturally appropriate care, and the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment all contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis and treatment among Asian American students,” she wrote over email.

Jhawar added that the expectation of Asian American students being high achievers in academics and their ability to follow through on that expectation can overshadow Asian Americans’ ADHD symptoms. She said teachers in elementary school settings are less likely to identify Asian children with ADHD symptoms if their grades are not unusually low.

“Because ADHD was long considered to be a disorder found in White boys, there is an inherent bias in the ways we research and diagnose ADHD,” Jhawar wrote over email. “Professionals tend to have a clear idea of what ADHD looks like in White boys, and a more murky understanding of how it presents in everyone else.”

But diagnosing the disorder in the first place becomes challenging after age 12, as ADHD symptoms can be confused for other mental illnesses or disorders. But even with a diagnosis, Asian American parents may be often reluctant to acknowledge or treat the disorder.

When Jiang got her diagnosis, her mother refused to medicate her seven-year-old child out of concern. Jiang had no choice but to adapt in the absence of treatment, and she unintentionally found useful coping mechanisms: instead of getting distracted during class and getting out of her seat, she could fidget with something small.

In order to complete homework, she would try to convince herself she was interested in a specific part of a school lesson to trick herself into hyperfocusing on completing assignments. At the core of it, she was suppressing her ADHD symptoms as much as she could.

Jamie Jiang at childhood. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Arthur Spota & Getty Images.

“When I suppressed (my symptoms), I did get punished less; I did get better grades,” Jiang said. “My parents were like, ‘Oh, cool, like it just flew away.’ So we all thought it was gone.”

Hearing from a high school counselor that ADHD doesn’t just vanish was eye-opening for Jiang, but it was doing more research and getting to meet other neurodivergent people in college that gave her the courage to get a diagnosis in America.

In her final year at UCLA, she ended up finding an Asian woman doctor at UC San Francisco who formally diagnosed her with ADHD through virtual meetings and prescribed her medication. Jiang said the psychologist, unlike other health professionals she saw in college, understood her as an Asian woman and the cultural nuances she had experienced throughout her life.

Jiang getting good grades did not mean she didn’t have ADHD, because she still struggled to achieve those scores despite of her symptoms, Jiang said. That fact that her therapist could see that too was important to her.

“She wasn’t doubting that an Asian woman could have ADHD,” Jiang said. “She was accepting of my China diagnosis as something that definitely had bearing on today.”

The cultural competency that Jiang noticed in her psychologist is key to providing care to patients, and it’s essential to understanding how ADHD symptoms manifest in people from underrepresented backgrounds.

“Having a culturally competent lens to interpret that information is incredibly important, because a lot of times, anxiety, ADHD and trauma — there’s a lot of overlapping symptoms there, and so being able to tease those things apart usually makes for a really good assessment,” said Nicole Enrique, a staff psychologist at Cal State Fullerton.

Photo courtesy of Jamie Jiang. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Getty Images & thevxlley.

Enrique also said that adults with ADHD can commonly look back and identify how they used to mask or suppress ADHD impulses, much like Jiang.

This was also the case for Ry Nakatani, a 21-year-old college student from Irvine, California. Growing up with conservative Japanese parents, the expectation to act normal meant being quiet and obedient and assimilating into the dominant society, they said.

However, Nakatani’s ADHD symptoms made it difficult for them to meet that expectation. They recalled, when they were younger, they combined two Japanese commercial jingles for potato chips and Saran wrap. They would repeat the melody continuously over the course of two and a half months. After their mother got tired of it, they started saying it in their head instead of out loud.

After receiving their ADHD diagnosis earlier this year, Nakatani said their psychologist determined they might have had more hyperactive traits when they were younger, such as repeating that jingle. However, this moment might have been the beginning of their internalization of their symptoms through masking to appear more normal.

Photo courtesy of Jamie Jiang. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Getty Images & thevxlley.

Dann Chen, a 51-year-old insurance salesman from Fullerton, California, said his formerly undiagnosed ADD affected how he saw himself throughout life.

When Chen was growing up, he said he didn’t do well in school. He said difficulties concentrating and frequently daydreaming led him to repeatedly get in trouble at school and at home.

He recalled feeling embarrassed after his teacher caught him staring outside the classroom windows instead of paying attention in class at his grade school in Massachusetts.

“It’s a funny thing, not really understanding and not knowing that, kind of finding yourself in a situation that all your classmates have finished everything and you’re still there trying to get started and it drove me up the wall because I would just be stuck there,” Chen said.

Chen said he dreaded parent-teacher conferences and report card day because he knew his parents would receive bad news about his performance in school. He recalled getting hit with a belt after they saw failing grades on his report card. In hindsight, Chen said he doesn’t blame his parents, who had immigrated from Taiwan, for not understanding what ADD or ADHD was.

“To them, all it was is that I wasn’t trying hard enough, I wasn’t disciplined to do the work. It was a matter of me not applying myself,” Chen said.

Chen said his self-perception became more negative later in life. Having poor grades made him feel like he was not equal to his peers. He said he did not finish college or receive a degree, which made him feel like a failure to his parents for not meeting the expectations placed on him. This self-doubt affected other areas of his life, like applying for jobs, meeting new people, wondering how he was perceived, and fearing being looked down upon.

“It compounded to become an issue that affected everything about me and who I am and who I grew up to be,” Chen said.

Vandana Ravikumar, a twenty-five-year old teacher from Carson City, Nevada, closed herself off from her family after they refused to believe she had ADHD.

Ravikumar told her parents about her growing suspicions of ADHD through email. After failing her AP Calculus exam, she tried to open up on how ADHD may have affected her test results. Yet, her parents continued to blame her for her own failure, saying she didn’t apply herself or pay attention. On top of that, she did not want to tell her brothers about her worries, but her parents told them anyway.

“It really hurt my feelings because I specifically told him I don’t want them to know about this, I don’t want to tell them, but it felt like it kind of came out without me wanting it to,” Ravikumar said.

After that, she hesitated opening up to her family in general. “I think as far as being really open about it with my family, it’s been something that I haven’t really felt comfortable doing,” Ravikumar said.

Despite not being formally tested for ADHD, Ravikumar looked into ways to get a prescription to treat her symptoms. While she was attending Arizona State University, her efforts were halted due to difficulties caused by her parents’ out-of-state insurance, forcing her to cope with her symptoms without treatment.

During her senior year in college in fall 2020, she wanted to be formally tested and treated for ADHD. Although she had reservations about the accuracy of the program, she finally received a formal diagnosis through a telehealth program, allowing her to access medication at 24.

“I would say it wasn’t like a huge change, but it was just kind of this undercurrent of feeling more confident in something that I’d already suspected, but just hadn’t had super solid proof until then,” Ravikumar said.

Photo courtesy of Jamie Jiang. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Behance.

The bonds between Asian American adults with ADHD and their parents are hard to repair because so much of it depends on the older of the two being willing to acknowledge the disorder, its symptoms and talk about it.

For Jiang, ever since she got diagnosed by the UCSF doctor in 2022, she has slowly been sharing information about ADHD with her parents, and in the process identified similar behavior patterns in them.

Every family outing Jiang can remember, both her parents were always late; her father has multiple layers of fail-safes to remind him of tasks he may forget; her mother accidentally lets eggs boil over in a small pot of water on the stove.

Although Jiang’s mother refusing ADHD treatment for when she was younger meant Jiang had to figure out coping mechanisms all on her own, she can recognize the care her parents had in making the decision. So in a sense, she’s getting to extend a similar kind of care back to them.

“It almost feels like I’m returning the favor for them,” Jiang said. “I know more about myself now, and that means I know more about you — I get to fill in these gaps that maybe you are struggling with.”

Photo courtesy of Jamie Jiang. Photo illustration by Macy Castañeda Lee. Clippings from Pinterest, re Emma Klee.

Feature

Washington, D.C. 2023

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.