Student work • Washington, D.C. 2023

Without the power to vote, some non-citizens are striving to get voters and non-voters alike to recognize and care about their political priorities.

Without the power to vote, some non-citizens are striving to get voters and non-voters alike to recognize and care about their political priorities.

Published July 21, 2023

Dhanika Pineda

Dhanika Pineda

Rachel Kim

Rachel Kim

Woojung "Diana" Park exercises her political voice.

Storystream

Read more from this series.

Woojung “Diana” Park is deprived of a fundamental liberty of American citizenship – the right to vote.

Born in South Korea, Park moved to the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant when she was one. The New York City resident comes from a mixed-status family; her younger sister has citizenship, while she and her parents do not.

Unable to cast her own vote in the 2020 presidential election, Park expressed her politics by steering her sister to support a more liberal campaign. This process of voting through others is one of many ways undocumented people are making their voices heard.

“A part of being undocumented is always being the silent supporter of other folks within this country,” Park said. “I think that’s the same when it comes to encouraging voter participation.”

Woojung “Diana” Park is one of the organizers behind the Our City, Our Vote campaign, which lobbies for noncitizens’ right to vote in local New York City elections. Photo courtesy of Diana Park.

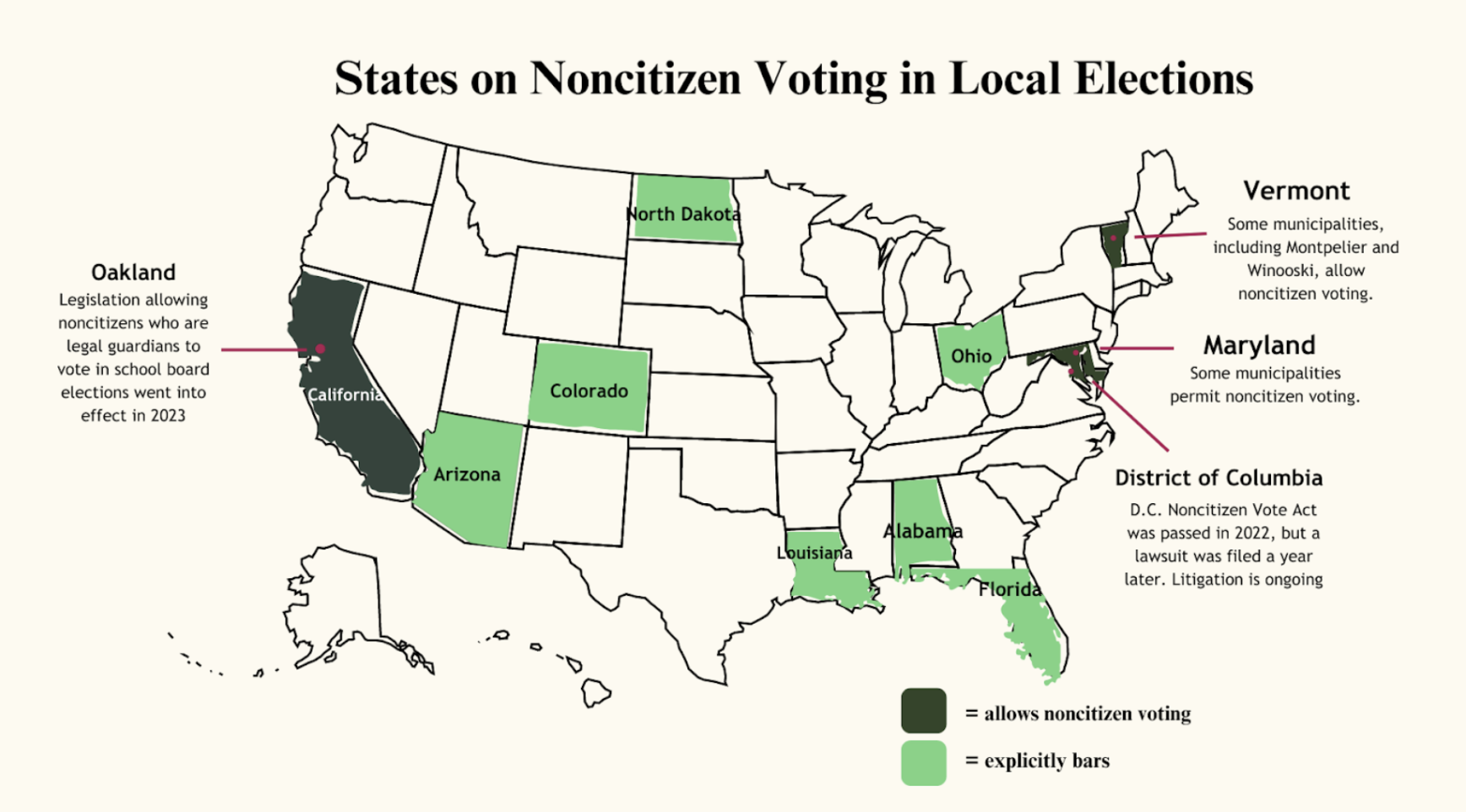

There are more than 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. as of 2019, the latest year for which data is available. Like Park, these immigrants were unable to vote in the 2020 federal elections and will remain unable to vote in those elections in 2024. While some municipalities – including Oakland, California and Montpelier, Vermont – have granted voting power to noncitizens in certain local races, several states have also explicitly barred them from participating in state and local elections.

Graphic by Rachel Kim. Source: Ballotpedia

Without the power to vote, some non-citizens are striving to get voters and non-voters alike to recognize and care about their political priorities.

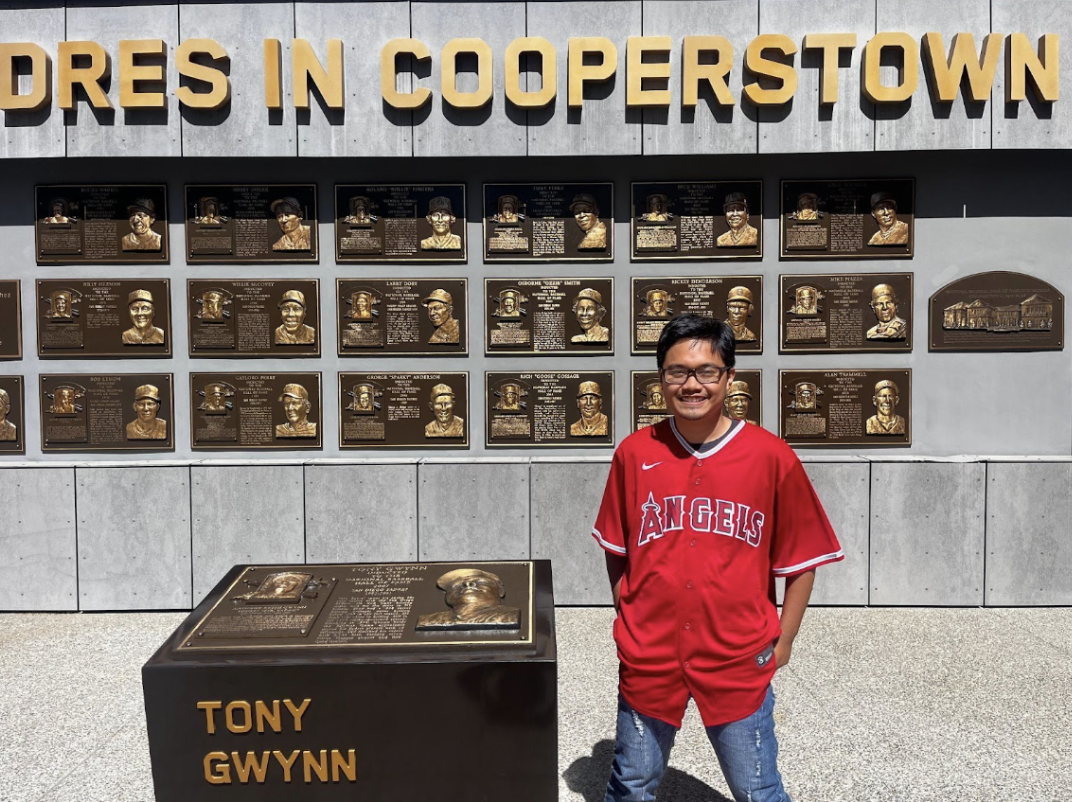

“We need to find people who understand and empathize with our plight and who will be willing to fight for us, fight for pathways to citizenship and footing in this country,” said Gabby Duga, an undocumented Filipino immigrant who moved to Glendale, California at 13. “But it would be so much easier if we could fight and vote for these things ourselves.”

Gabby Duga moved with his family from Cavite, Philippines, to Los Angeles at 13. Photo courtesy of Gabby Duga.

The New York City Council approved legislation in December 2021 that would give approximately 900,000 eligible noncitizens the right to vote in local elections. But in a blow to immigration advocates and undocumented residents, a state judge ruled it unconstitutional after Republican leaders filed a lawsuit against the bill.

In response to the overruled court case, Park and other immigrant rights activists are organizing rallies around voting rights for noncitizens, as well as the legality of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

“We are conditional citizens,” Park, who is a DACA recipient, said at a June 2023 Our City, Our Vote coalition rally in front of the New York State Supreme Court. “It is difficult, but it’s a fight that we will continue.”

Duga echoed her sentiment from the opposite coast. “As undocumented people, we carry both the shame and burden of being at the mercy of a federal government whose decisions we have no say in and who frankly do not seem to want us here. We deserve to have a voice, to have a say in those decisions too,” he added.

When undocumented community leaders do voice their concerns, it can be challenging for them to be heard. Immigration is not as top of mind for eligible voters as it is for immigrant rights organizers.

In a 2022 survey of Asian American voters nationwide, only about a third of respondents identified immigration as an extremely important issue, and a similar share strongly agreed that undocumented immigrants should eventually be able to gain citizenship.

Graphic by Rachel Kim. Source: Advancing Justice – AAJC

“Because we don’t have the right to vote, we have to beg for things that many of our documented counterparts take for granted,” Duga said. “People tend to forget the plight of the undocumented or have other priorities on their mind when it comes to voting.”

As they brace for the 2024 election, Duga hopes voters keep a few key issues surrounding the rights of undocumented people in mind, including: authorizing legal hiring for undocumented people on a national level, expanding access to healthcare and processing new DACA applications.

Undocumented organizers have seen some success around these priorities. In October 2022, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) ruled that new DACA requests cannot be processed, eliminating new “Dreamer” recipients. That means that non-Dreamers’ only legal employment option is contract work. In response to the DHS ruling, undocumented students across the University of California system successfully led a campaign to legalize labor for undocumented students on UC campuses.

Rehana Morita, a student leader for the O4A campaign and a non-DACA recipient herself, has experienced firsthand the difficulty of securing employment.

“It’s a lot different, especially as a student, to have to constantly be thinking about whether or not certain opportunities will be accessible to you,” said Morita, a Japanese citizen who moved to California’s Inland Empire when she was seven.

Securing such victories at the national level, however, has proved more challenging.

Since being elected to office in 2020, President Joe Biden has yet to fulfill his campaign promise of granting legal pathways to citizenship for more than 11 million undocumented people. Biden has made some immigration reforms, including expanding health coverage of DACA recipients and increasing the number of eligible immigrants under the Temporary Protected Status program. But his proposed U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, which would allow undocumented immigrants to apply for temporary legal status if they meet certain criteria, has yet to passs.

Even if landmark legislation passed and granted legal status to undocumented immigrants, change wouldn’t be immediate. Community organizers expect a painstaking wait for results of pending asylum cases, unprocessed backlogs and court cases for legislation like Our City Our Vote.

Doing this work is not without risks. For undocumented people, action and advocacy often come with fear.

“There is that fear of ‘If you talk too much about your situation, you’re gonna get yourself out of the country,’” said Duga. “At the end of the day, we have to have the courage and the fortitude to do this because we’re the ones who can change this country for [better or worse.]”

Even though it might be risky for them to stand up and fight for their rights, Park does it for the millions of others in the US who are also navigating life as undocumented immigrants.

“We make a point when we show up and gather together. That’s where I get my strength from – knowing that I’m not the only one that wants this,” said Park. “I think to myself, if not me, then who will?”

Dhanika Pineda is a recent graduate from the University of California, Irvine, where she founded an alternative student newspaper, The AntReader, to combat censorship and ill-treatment of the student journalists of official campus newspaper, The New University, which she served as Editor in Chief of. She is the Featured Stories editor at Kapwa Magazine, a Filipino cultural publication. She has previously written for Orange Coast Magazine, UC Irvine News, and the nonprofit organization We Need Diverse Books.

Rachel Kim is a recent graduate from New York University with a B.S in Media, Culture and Communications. At NYU, she has written for HerCampus NYU, IR Insider, and the travel magazine Baedeker. She recently completed her study abroad in Seoul National University where she served as video team leader at The Quill and published short features articles.

Washington, D.C. 2023

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.