Feature

Student work • Washington, D.C. 2023

Chinatowns in Philadelphia, Manhattan, and Los Angeles are trying to shape their own futures in the face of adversities.

Chinatowns in Philadelphia, Manhattan, and Los Angeles are trying to shape their own futures in the face of adversities.

Published July 21, 2023

Anne To

Anne To

Emi Tuyetnhi Tran

Emi Tuyetnhi Tran

Jane Zhang

Jane Zhang

Kathy Ou

Kathy Ou

Residents of New York City protest the construction of a "mega jail" in Chinatown in 2019. (Credit: Cindy Trinh via Neighbors United Below Canal)

In May, Chinatown leaders across North America met in Vancouver with one goal: How can they preserve their cultural spaces?

“There was this kind of affection, this feeling of support,” said Carol Lee, chair of the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation. “We’re all doing different things, but we’re facing similar challenges. And I think that that was in some ways kind of comforting.”

Emerging in the late 19th century when migrants came to North America to build railroads, Chinatowns have been a source of community, protection and a vital place for essential services and cultural heritage. But urban redevelopment, rising housing prices and displacement of long-term residents threaten those enclaves.

In 2023, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Philadelphia’s Chinatown one of the nation’s top endangered historical sites. In Manhattan, New York City, the community banded together to try to block a 300-ft mega jail slated to be built in Chinatown. And in Los Angeles, community advocacy groups have presented competing visions for the future of Chinatown.

“We were all surprised that it didn’t matter where you were in Canada or the U.S. So many of the issues are common,” Carol Lee said. “I’m always amazed at how much people do with often very little. It’s in the DNA of the neighborhoods from the very beginning, how to succeed against improbable odds.”

Here’s how different groups of activists and stakeholders in three Chinatowns in the U.S. are trying to shape their future.

On June 10, Kaia Chau clasped a bullhorn next to a U-Haul truck in the middle of a Philadelphia street, leading a community march against the proposed 76ers stadium and yelling “Hands off Chinatown!”

Chau, a rising senior at Bryn Mawr College, wore a white t-shirt printed with the phrase “NO ARENA CHINATOWN.” The term “arena” covers the words “stadium” and “casino,” alluding to previous attempted developments in the neighborhood in the last two decades. Also included were Chinese characters for those slogans: 不要棒球场 (bu yao bang qiu chang) / 赌场 (du chang) / 篮球场 (lan qiu guan).

Hours later, Chau’s mother, Debbie Wei, was half a mile away at Philadelphia City Hall, chanting, “We don’t trust the process.”

Wei, who founded Asian Americans United (AAU), was a prominent figure in protests against a Phillies baseball stadium in Chinatown in 2000 and again in the 2008 fight against a casino in the neighborhood. Twenty years later, she works alongside Chau to prevent the construction of another potentially disruptive sports stadium in the city’s ethnic enclave.

“I think the intergenerational nature of our fight is something that I think serves and resonates with people.” —Debbie Wei

A third-generation Chinese American, Chau is a Philadelphia Chinatown native who attended Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School, founded in 2005 by AAU as a K-8 school for the city’s Asian American communities with, according to Chau, an emphasis on respecting “the elders who fought to preserve Chinatown.”

In October 2022, Chau co-founded Students for the Preservation of Chinatown with her childhood best friend, Taryn Flaherty, who went to the same charter school as Chau. SPOC has organized dozens of rallies and garnered thousands of supporters on social media.

“[Taryn and I] weren’t alive for the stadium fight, but we were alive for the casino fight,” Chau said. “That’s sort of like the environment that we grew up in and the moms we grew up with.”

Kaia Chau and Taryn Flaherty at the June 10 demonstration at City Hall. (Credit: Joe Piette)

On June 10, thousands marched from Chinatown to City Hall, marking nearly a year since the managing partners of the 76ers and apartment developer David Adelman announced that they intended to build an arena in Philadelphia’s Fashion District, just a few blocks away from Chinatown. Just days before the planned demonstration, the company representing the 76ers had released the first drawings for a stadium design.

Philadelphia’s Chinatown, home to just over 2,500 residents, represents a safe haven for people like Chau’s grandparents, who immigrated to the U.S, Chau said.

But an influx of sports goers would cause issues for Chinatown’s residents and businesses, such as traffic buildup and rowdy crowds, Chau said.

“Even though I’m a very big Philly sports fan, I will acknowledge that after games, a lot of drunk sports fans are around, and it’s just not a very safe environment for the elderly to be around, for children to be around,” Chau said.

A crowd of people marches from Chinatown to City Hall, opposing the plans to build an arena in the district on June 10. (Credit: Joe Piette)

Despite promises that they would consult the local community, a real estate company developing the arena has not consulted residents, activists said.

“Mayor [Jim] Kenny and Councilman [Mark] Squilla both promised us that if the community didn’t want it, it would not happen,” Wei said.

The preservation of Chinatown in Philadelphia has always had an intergenerational focus, activists said. At the demonstration in June, speakers included a slew of high school and college students, as well as Chinatown resident Kai Chung Chin, 96, who marched a half mile to speak at City Hall about preserving the neighborhood for the younger generations.

Resilience and an undying spirit were the key to Philadelphia Chinatown’s survival, according to organizers. And organizers believe that’s still the key to success today. Wei wants to preserve a Chinatown for her children and their children to be able to enjoy — the same values and aspirations that Chau grew up surrounded by.

At the end of “Look Forward and Carry on the Past,” a 2002 documentary about community resistance against constructing a baseball stadium in Chinatown, Wei had a message for the generations to come.

“Even though we won the fight against the stadium, it’s going to be a continual battle for the right for the community to exist, to exist with dignity, having the things a community should have,” she said. “And we’re going to fight it, and then my children are going to have to fight it as well.”

In August 2018, Manhattan’s Chinatown leaders gathered in the community room of Chung Pak Everlasting Pine, a low-income senior housing built as a concession to the neighborhood for the construction of a jail 25 years prior.

They had been called to the meeting by New York City Council Member Margaret Chin’s office and were told the news: A 40-story mega jail would be built in the neighborhood, as part of then-Mayor Bill de Blasio’s $8.3 billion plan to shut down Rikers Island’s facilities and replace them with a borough-based “network of modern, safe and humane” prisons.

The leaders, including third-generation Chinatown resident and landlord Jan Lee, were given two choices for the site. But within two weeks, the city had already made a decision. The towering Manhattan jail would be built at 80 Centre Street, atop a nine-story government office building and just blocks away from another long-standing jail, the Manhattan Detention Complex, also known as the Tombs.

“What we thought was a choice wasn’t a choice,” Jan Lee said.

A fight against the Goliath was ahead of them.

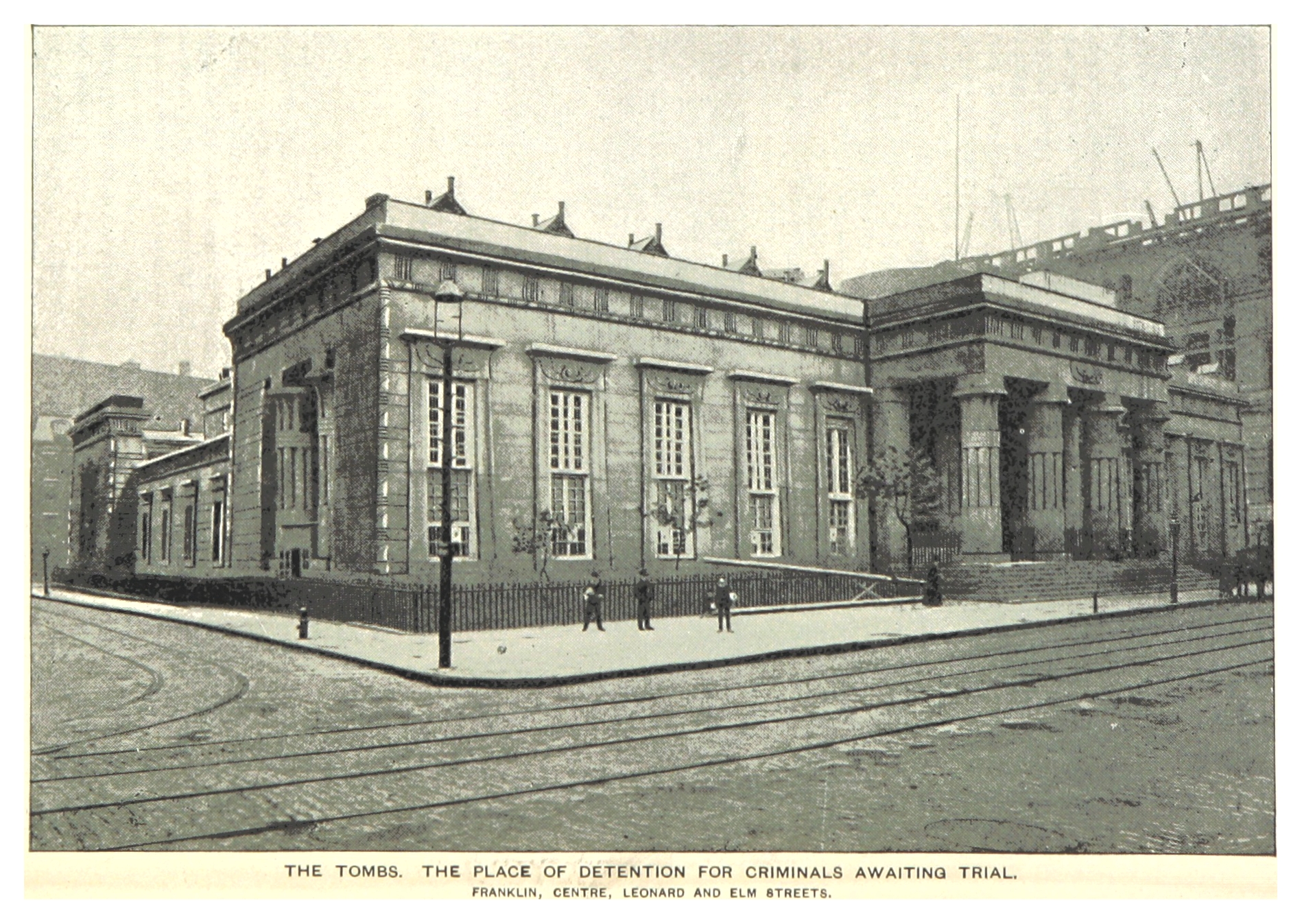

Jails have been a constant part of Manhattan’s Chinatown’s history. In the 1870s, Chinese immigrants began settling around Mott Street in Lower Manhattan, just blocks away from the New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention, constructed in 1838.

The original Tombs building. (Credit: British Library / Wikimedia Commons)

As Chinatown developed over the decades, so too did the jails within it. The jails reincarnated several times over: City Prison in 1902, the Manhattan House of Detention in 1941, and the Manhattan Detention Complex in 1983.

Some 12,000 demonstrators protested in 1982 against the plan to open the Manhattan Detention Complex, nearly a decade after the previous jail was shut down due to its notoriously horrid conditions. The protest ultimately failed to stop the construction, although the city agreed to a few concessions for the community, such as building Chung Pak Everlasting Pine.

Chinatown residents protesting the reopening of the Tombs at a rally on Nov. 18, 1982. (Photograph taken by Emile Bocian, Museum of Chinese in America Emile Bocian Collection)

Jan Lee remembered growing up in the shadow of the Tombs as a young child, playing in Columbus Park half a block from the jail’s entrance.

“What I can tell you is psychologically, living among the Tombs is not healthy for the neighborhood,” he said. “For a lot of my childhood, I saw Black and brown men taken out of police cars in handcuffs and walked down the streets of Chinatown, waiting to enter the Tombs. That’s not normal. And that doesn’t happen in white neighborhoods.”

That kind of experience, Jan Lee said, is unfair to the detained individual, who is supposed to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, as well as to the children and elderly in the park, who have to witness it.

Following the jail plan announcement in 2018, Jan Lee and other community members including neighbors, businesspeople, and other stakeholders created Neighbors United Below Canal (NUBC) to understand and reflect the community’s needs, as well as to consolidate and disseminate information about the jail construction.

The community had worries about the proximity of the jail site to Columbus Park as well as structural safety concerns about constructing the jail on top of an existing building.

“Some of the loudest and most well-attended opposition that I’ve ever seen in Chinatown was because of this jail.” —Jan Lee

Residents at a protest on Oct. 6, 2019 rallying against the plan to construct a mega jail in Chinatown as part of Mayor de Blasio’s borough-based jail project. (Credit: Cindy Trinh via Neighbors United Below Canal)

In November 2018, the city reversed its decision on the location, instead slating the Tombs for demolition to build the mega jail there instead and saying that the change was due to logistical challenges with relocating various government offices.

In 2020, NUBC sued the city over what the organization considered to be an improper land use approval process, concerned about how the construction of the jail would clog up the neighborhood’s traffic and pollute the area’s air. A judge ruled in favor of NUBC in September 2020, but the decision was overturned by an appellate court in 2021.

NUBC then proposed that the Tombs’ existing structures be reutilized — a process known as adaptive reuse — rather than demolishing and reconstructing them, but this idea was rejected by the city.

Despite their ongoing efforts, Jan Lee believes the jail is going to be constructed. “We accept grudgingly and under protest,” he said. But, he added, the Chinatown community must be included in the conversation. Otherwise, they will protest.

“We will yell. We will get arrested. We will do everything we can to name you who are standing in our way of a safer Chinatown.” —Jan Lee

This doesn’t mean, however, that the community does not care about criminal justice reform.

“We also need to look at the atrocities that are being committed on Rikers,” said Victoria Lee, co-founder of Welcome To Chinatown, a nonprofit organization that works with small businesses and entrepreneurs to preserve the community. “But on the flip side of that, that doesn’t also mean that the community, like Chinatown, should be harmed in this process too.”

And constructing a new mega jail in Chinatown will not solve the city’s problems with its criminal justice system, said Jan Lee.

When the Tombs reopened in 1983, it was heralded by officials as “one of the most humane and efficient jails anywhere.” Its predecessor had been described as “a miracle of modernity” at its opening in 1941. Yet problems have persisted throughout.

The new mega jail in Chinatown — likely to be the tallest jail in the world at nearly 300 feet — will be a “state of the art facility” that is “designed to foster safety and wellbeing,” according to the city.

Instead, the community wants the funding to be funneled into the neighborhood, such as mental health resources and housing solutions.

“What we’re saying is, stop this cycle.” —Jan Lee

It’s unclear what the future holds for Chinatown, but the fight will rage on.

The many hits that the community has faced, such as the recent rejection of the adaptive reuse plan, do not signify failure to Jan Lee. The adaptive reuse plan united all elected officials representing Chinatown, he said. Chinatown has also built solidarity with other communities of color, such as the Bronx, a predominantly Black community fighting the construction of its own borough-based jail.

“We have to say to our elected officials we’re ready to take to the streets again if things don’t go our way,” said Lee. “We need a seat at the table, we want an independent monitor and we want proof that this is going to be done safely. And unless we get all three of those things together, then they’re going to have the answer to whatever action we take.”

Below red lanterns and LED store signs, thousands of attendees funneled through the annual KCRW Summer Nights in Chinatown event in Los Angeles’ Central Plaza, dancing to the EDM and pop music mixed by the radio station’s DJs on stage.

Alongside the brick-and-mortar gift shops selling party poppers, bubble wands and rice hats, dozens of food trucks and vendors – many not from Chinatown and drawing crowds through social media – filled the plaza.

Selena Jackson and Taylor Sietsema had barely visited Chinatown before the event, hearing about it through a friend who was one of the DJs for the night.

“I’m a little overwhelmed, but it’s honestly really fun,” said Jackson, who bought three things at a gift store “the minute” she and Sietsema walked in.

The event sought to attract visitors like Jackson and Sietsema who had rarely visited Chinatown, hoping they would return, said Shirley Zhang, a project coordinator of the city’s Chinatown Business Improvement District (BID) who hosted the event.

Lanterns strung over Sun Mun Way guided attendees to the main stage along with art stands, food trucks, and stalls on June 24. (Credit: Kathy Ou)

Months ago, however, another community group sought to present their own vision of Chinatown.

“Get ready for Chinatown’s OWN neighborhood night market,” posted Chinatown Community for Equitable Development (CCED) on their social media post prior to the event. “[An] event by and for the community highlighting the shops at Dynasty Center, and not for the BID and its gentrifying interests.”

At a corner of a parking lot at Chunsan Plaza on Broadway Street, a vendor sold roast duck. The back of the market smelled of dim sum and spicy popcorn chicken. People grabbed the mic at a karaoke station at the entrance, singing songs in Cantonese, Mandarin and other languages with a lion dance at the end.

Many elders and local residents were there, so did four businesses from Dynasty Center. Chinatown’s largest indoor swap meet was sold in 2021 to a real estate company Redcar Ltd. who had given tenants verbal and informal eviction notices with shifting timelines given by the property manager.

The night market was also a response to the KCRW Summer Nights in Chinatown. CCED has previously spoken out against Summer Nights and BID, pointing out the hypocrisy in BID’s stated mission to support local businesses while only a handful of Chinatown-based businesses were included in the long vendors line-up.

At one of last year’s Summer Nights, CCED protested with disruptive chants and banners.

Attendees shopping around at the Chinatown Neighborhood Night Market on March 18. (Credit: Kathy Ou)

Both the BID Summer Nights and the CCED Night Market brought together people in Chinatown and provided opportunities for extra business to the local community. However, they represented two drastically different visions for what Chinatown could become.

While BID and its supporters envision a Chinatown revitalized with new popular stores to attract outside interest, CCED and its supporters want to preserve the neighborhood as a haven for its predominantly low-income working-class immigrant communities.

Small businesses in Los Angeles’ Chinatown today reflect this division. The older, legacy businesses owned by Chinese, Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrants contrast with newer shops including restaurants with celebrity chefs, wineries and art galleries.

Established by a group of community members and stakeholders in 2012 to oppose a Walmart moving into Chinatown, CCED has organized both commercial and residential tenants — most of whom were Asian seniors. Since the pandemic, CCED started to build relationships with local businesses, especially restaurants as the organization also ventured into mutual aid.

“Chinatown was an ecosystem of low income migrant folks supporting each other,” CCED organizer Annie Shaw said. “We’re here to foster that relationship again, but also to build community power to make the changes that need to be taking place.”

Legacy businesses provide essential goods at affordable pricing as well as employment opportunities to many immigrants living in Chinatown who rarely find jobs elsewhere, said Sissy Trinh, the executive director of Southeast Asian Community Alliance (SEACA), a Chinatown nonprofit focused on youth organizing and community development.

“To push them out and replace them with a chain business, you don’t get that kind of relationship and that sense of community,” Trinh said.

But Zhang of BID sees it differently, saying L.A. Chinatown’s identity depends on tourism which means attracting hip businesses.

Consisting of a group of local property owners, BID collects special assessments to fund streetscape improvements and promotional activities. BID spends most of its money on sidewalk cleaning and hiring officers to patrol the neighborhood 24/7 for “safety,” Zhang said.

With clashing ideals and practices, individuals and businesses in Chinatown have ambivalent relationships with both BID and CCED.

Alex Cheung, 74, is the owner of Alex Cheung Antique, the last legacy business that is still operating on Chung King Road which has become a hotspot of the city’s contemporary art scene.

Cheung said he appreciates CCED’s outreach to legacy businesses like his. But over the past five years, he came to terms with the fact that regardless of the history and glorious past of his shop, it would not survive forever.

“There is no future,” Cheung said. “I’m just here killing time.”

Opened in 1933, Jin Hing Jade Jewelry has withstood the plunge in Chinese-owned businesses in recent decades. Many new businesses have appeared, but few stick around.

Unlike many business owners in the neighborhood who don’t own the properties, Robert Lee owns his. Still, he shared the sense of resignation that Cheung feels about Chinatown. Robert Lee has not even joined the BID because of a lack of time and energy.

“The problem with a lot of the shopkeepers, including myself, is you’re so busy with your own business that sometimes you don’t know what’s happening. In fact, you don’t know what’s happening with your neighbors,” Robert Lee said.

Geoffrey Kixmiller, one of the two co-owners of Tomorrow Today bookstore and a white man who grew up in Brooklyn, New York, had volunteered with CCED before in solidarity and to understand how his shop can be a resource for the group’s organizing.

But CCED cut off communication when he opened the store in Chinatown in September 2020, eight months after taking over the lease. He realized: CCED sees him as a “gentrifier” too.

Kixmiller said it was a hard lesson for him, but accepts CCED’s criticisms. However, he also believes in the value of his store.

Developers are charging such high commercial rent that even new essential businesses such as grocery stores would struggle to be affordable to the community, said Elise Dang, the co-chair of CCED’s Small Business Committee.

“We’ve had a couple of new businesses approach CCED asking how they can minimize their damage on the community, and we’ve told them that the best way is to either leave or not move into Chinatown unless their business can provide an essential product or service that is accessible to the local community,” said Dang.

But Trinh believes there are steps individuals can take when they run a business in the neighborhood, as enumerated in a community pact Trinh wrote on SEACA’s blog in 2022. However, no matter how much work or good intention these “hipster businesses” had, Trinh said not everything is within their own control.

“They [hipster businesses] are not doing anything evil, like trying to evict people, but their presence emboldens the real estate speculators to do so. That’s the issue,” Trinh said.

Confetti paper littered the concrete ground of Central Plaza on June 24. (Credit: Kathy Ou)

**Prior to reporting on this project, Kathy Ou has volunteered with CCED for a year. She was no longer involved with the organization while reporting this project. She did not conduct interviews with the CCED sources.

Anne To is a rising senior at the California State University, Los Angeles, where she is studying Journalism and Creative Writing. She is a summer archiving and programming intern at the KQBH 101.5 FM, the editor-in-chief of the University Times and the co-station manager of the Golden Eagle Radio.

Emi Tuyetnhi Tran is a rising senior at the University of Pennsylvania, where she is studying Political and Moral Philosophy. She is a summer intern at the NBC News and executive editor at The Daily Pennsylvanian.

Jane Zhang is a master’s student at New York University, where she is studying Global Journalism and International Relations.

Kathy Ou is an incoming master’s student at New York University, where she is studying Cultural Reporting and Criticism.

Feature

Washington, D.C. 2023

Apply

Become a fellow or editor

Donate

Support our impact

Partner

Work with us as a brand

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) is a membership nonprofit advancing diversity in newsrooms and ensuring fair and accurate coverage of communities of color. AAJA has more than 1,500 members across the United States and Asia.